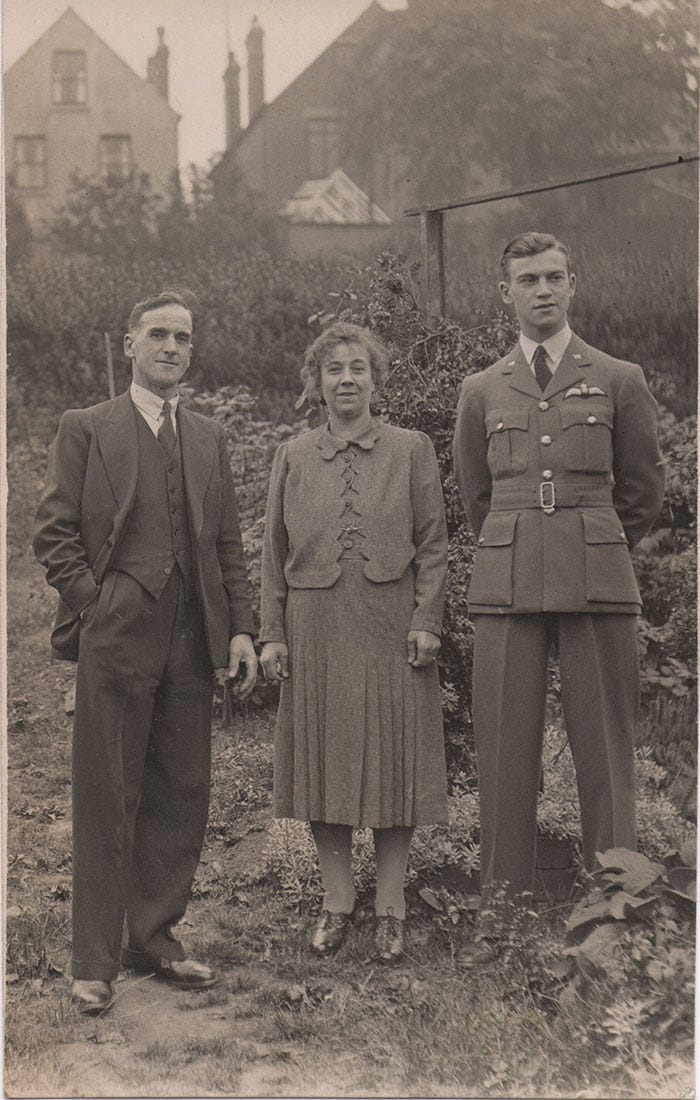

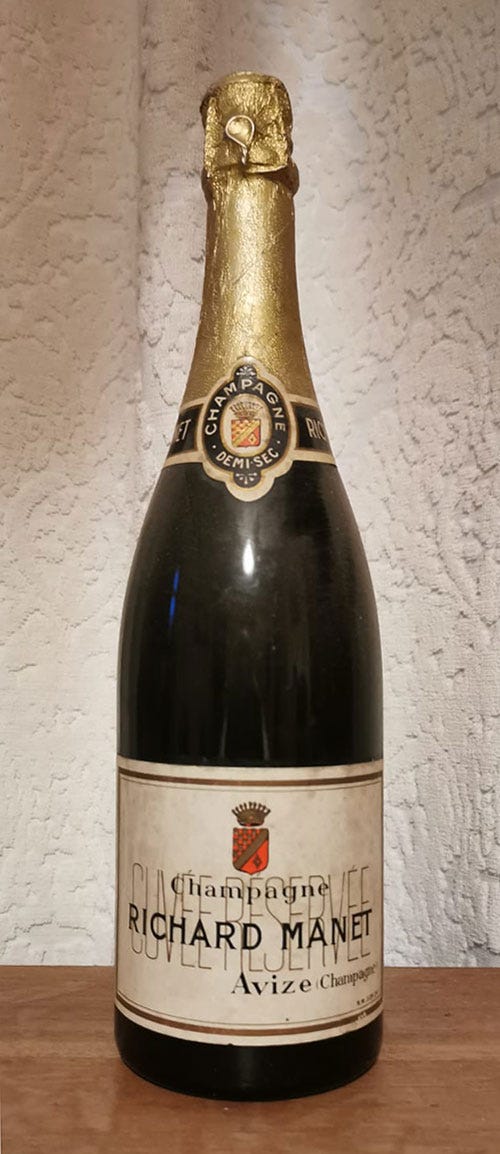

Looking for a tipple to celebrate Christmas 2020, Mum recalled seeing a bottle of champagne in the cabinet. My brother Robin, who was caring for our parents at the time, retrieved it and was puzzled by the dusty label. It dawned on Dad that this was the champagne his Aunt Florence and Uncle Arthur had kept to celebrate the safe return from World War II of their only son, Arthur Gordon Richardson (known as Gordon, to differentiate him from his dad), an RAF Spitfire pilot.

It was never opened. Gordon’s plane was shot down over occupied Holland on January 22nd 1945, while dive-bombing an oxygen factory near Albasserdam (liquid oxygen was used to fuel German V-2 rockets). He was 26.

He was Dad’s only cousin and his death had a profound effect on Dad, who was only 14 at the time.

Mum and Dad brought the champagne home, along with Gordon’s photo albums and other mementos, when they cleared Florence’s house in Sheffield after she died in 1984. Later, I helped Dad apply for a copy of Gordon’s war record. Here’s what I’ve learned.

Grandson of an inventor

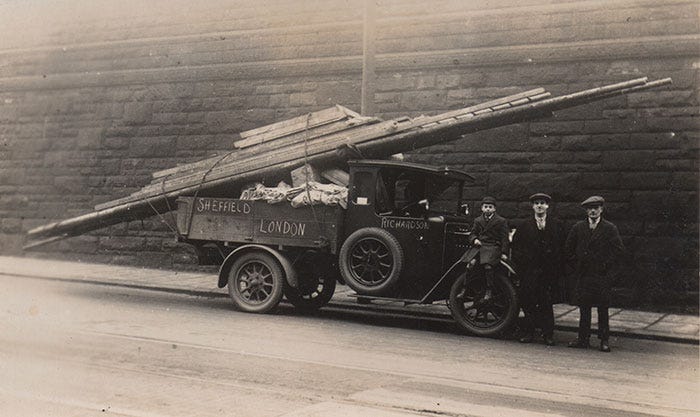

Gordon’s grandfather, Charles Ebenezer Richardson1, produced the Richardson car in 1919, and invented the popular toy, the Finbat, a bat with ball attached by elastic. His father, Arthur Reid Richardson, ran a haulage company.

Artist, writer, photographer

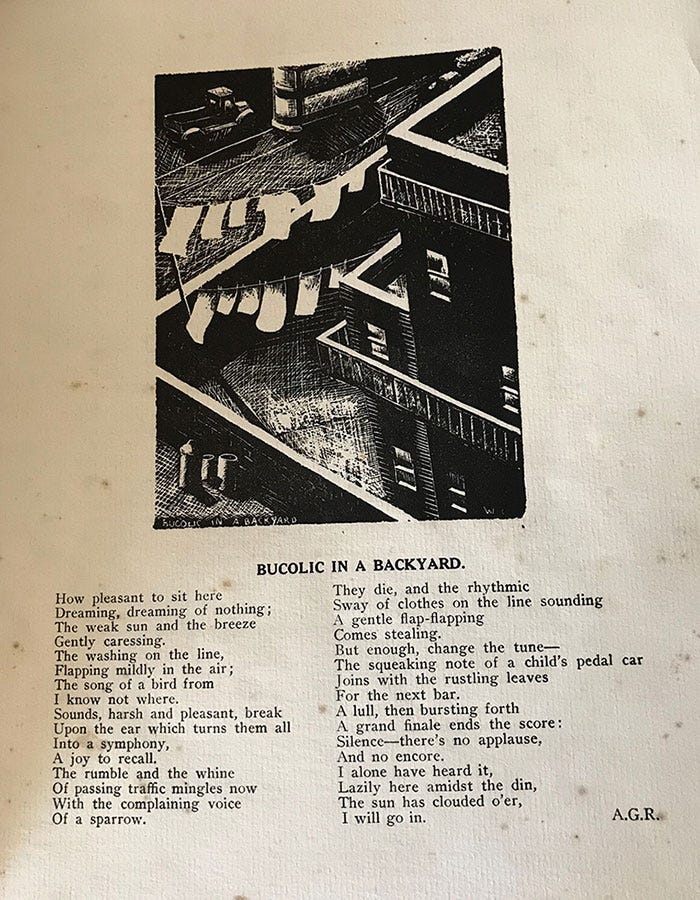

Gordon was educated at High Storrs Grammar School for Boys in Sheffield. He played football and performed in musical productions. This excerpt from the school magazine, titled Bucolic In A Backyard, shows him to be a talented artist and thoughtful writer.

How pleasant to sit here

Dreaming, dreaming of nothing;

The weak sun and the breeze

Gently caressing.

The washing on the line,

Flapping mildly in the air;

The song of a bird from

I know not where.

Sounds, harsh and pleasant, break

Upon the ear which turns them all

Into a symphony,

A joy to recall.

The rumble and the whine

Of passing traffic mingles now

With the complaining voice

Of a sparrow.

They die, and the rhythmic

Sway of clothes on the line sounding

A gentle flap-flapping

Comes stealing.

But enough, change the tune –

The squeaking note of a child’s pedal car

Joins with the rustling leaves

For the next bar.

A lull, then bursting forth

A grand finale ends the score:

Silence – there’s no applause,

And no encore.

I alone have heard it,

Lazily here amidst the din,

The sun has clouded o’er,

I will go in.

He qualified as a teacher at Sheffield Teacher Training College. I’m not sure what he specialised in, but judging by the quality of his drawing and photography, perhaps it was art.

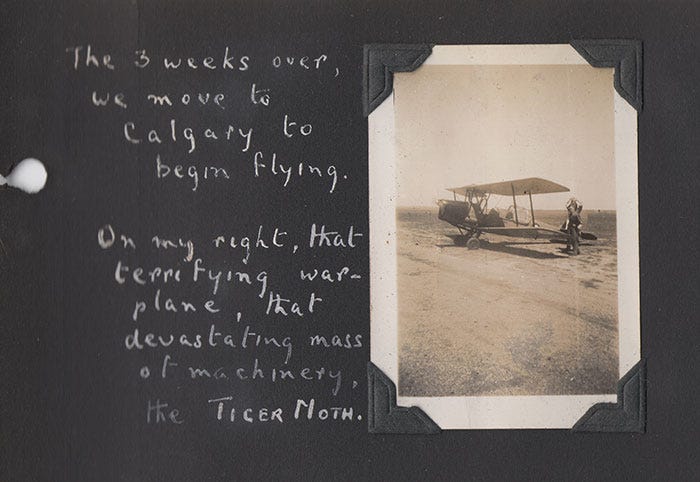

After he enlisted in 1940, Gordon’s RAF flight training took place in Calgary, Canada. His photo album shows him exploring the country in his free time, playing softball, horse-riding, skiing, canoeing, and visiting the Calgary Stampede. As well as flying, of course.

The accident

By Summer 1943, Gordon was based in the Egyptian desert with 74 Squadron. The squadron log book for 17th July 1943 states:

“F/O. Richardson had a nasty accident, burning himself pretty badly whilst ‘de-lousing’ the tent with petrol.”

Gordon had absent-mindedly walked back into the petrol-soaked tent holding a lit cigarette.2 He was sent to hospital in Alexandria with severe burns. His injuries meant that once he recovered, he could have switched to clerical work. Instead, he returned to flying, based in the Middle East, then joining 127 Squadron3 in England in April 1944 as a Spitfire pilot.

A last visit home

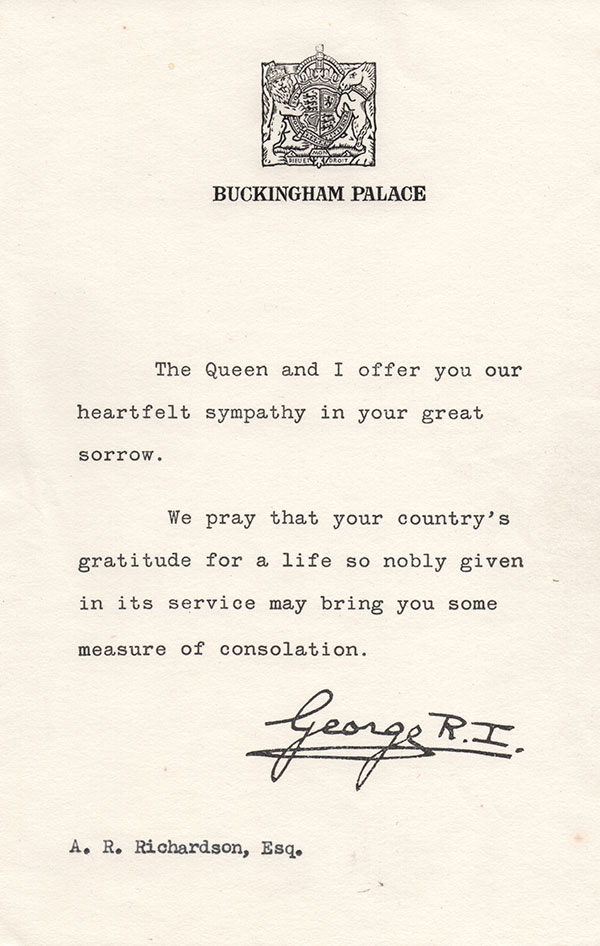

My Dad remembers seeing Gordon for the last time when he was home on leave for Christmas 1944. A month later, he died. His father received a letter of condolence from King George VI.

When my Mum, Betty Varley, found the mementos in Gordon’s old bedroom after his mother died in 1984, she wrote:

“I thought of the promise in that happy young face; and I remembered and looked again at the carefree, and happy smiles, of his mother with her young son, his father proud and confident.

“I remembered the remarks overheard – ‘She couldn’t bear to have his uniform in the house – she was in hospital – by her own choice – she never got over it.’

“The champagne bought for his return was never opened. Some day, perhaps we will drink; and when we say ‘We will remember them’ we’ll think not only of the wonderful vital men and woman who were killed, but of the Mums and Dads who suddenly died inside: in some ways theirs was the harder task of trying to pick up the threads of existence; of plodding on with secret tears and cold uncomforted hearts for forty empty years.” (Betty Varley, 1984)

My brother has kept the champagne, in memory of Arthur Gordon Richardson: 18th May 1918 – 22nd January 1945.

Why have I written about Gordon? Firstly, because since my Dad died aged 93, I doubt there’s anyone left who would have known Gordon. I’ve become the “keeper” of his story. If I don’t tell it, no-one will, and I know it would have meant a lot to my Dad that I share it.

Secondly, my son is 23. I think about shifting geopolitics and wonder what’s around the corner.

Thirdly,

has been publishing her grandfather’s RAF memoirs on Substack, and that spurred me into research mode!Over to you: are you a “keeper” of a story that might fade from history if you don’t tell it? Please do comment if you’re able. I love to hear your thoughts.

Thank you to everyone who responded to my piece last week, My quest for a tiny waist. Reading your amazing comments I wonder whether any of us haven’t wrestled with food- and body-issues at some time in our lives. And it’s not just women. I was pleased that Stephen Short (

) used it as a prompt to tell his own story, which you can read here.Clicking the heart, commenting and/or sharing this piece will help other people find my writing.

Thanks for reading, and if you haven’t already subscribed, I do hope you will!

Or, if you wish, there is a Wendy’s World tip jar:

Until next time!

© Wendy Varley 2025

C. E. Richardson and Co were based at Finbat Works, Aizlewood Road, Sheffield.

“[At] the airfield 74 [Squadron] had just moved in to – El Daba – … the tented living areas were infested with fleas. The Medical Officer found that the most effective way of dealing with them was to remove the contents of the tents, seal them and soak the ground with petrol. After a while the tents would be reopened and the sides rolled up so that air could circulate through them and thus remove the smell.

“Apparently it worked well – but Gordon, having soaked the ground of his tent with petrol, forgot himself and went back inside whilst smoking. The tent exploded in a fireball and he was badly burned.”

Email received from Secretary of 74 Squadron, 8 February 2010, after I wrote to ask if there was any more detail of Gordon’s accident aside from what was in the log book.

I am grateful to Andy Ingham for information he sent me about 127 Squadron.

What a beautiful story, Wendy. That bottle of unopened champagne is heartbreaking. Poor Gordon and his parents, and others who loved him; your father. How terribly young he was.

My father was a Pilot Officer with the RCAF 409 Squadron. Night fighters, flying Mosquitos. He crash landed three times during WWII. Once in Saskatchewan during training, once in Lille, France in 1944 and once on the border of Holland and Germany in 1945.

He was one of the lucky ones and was coming home on a troop ship for a short leave before being sent to the Pacific war when Hiroshima / Nagasaki were bombed, the Japanese surrendered and the war was over.

His memoirs include references to the crews of downed planes that didn't make it and one particularly thought provoking telling of a burial at an airfield.

When he was in his fifties and suffering from debilitating neck pain, he went to our family doctor to figure out what was wrong. The Doctor asked him if he had been in any accidents. My father thought about it and then said, "Do plane crashes count?"

He lived to be 96, sore neck and all.