The WWII evacuee and her precious violin

My mum was one of 800,000 British children evacuated from cities to the countryside at the start of WWII. She was away for four years. Here’s her story.

At nine years old, my mother said goodbye to her parents, took her four-year-old sister by the hand, boarded a train and travelled with hundreds of other children from Birkenhead to rural Wales. The date: 2nd September 1939. Their evacuation was to shelter them from the coming bombing raids on Merseyside, which was a major German target during World War II.

While many of the 800,000 evacuated British children returned home relatively quickly, feeling homesick, Mum and Jean stayed in Newtown, Wales, for four years – most of the war. They lived first with Mr Sawer the dentist and his family, then with the Woollies, on a farm. (I’m noticing some nominal determinism here!) They were well-cared for by their foster families. Their parents back home contributed to their upkeep via a government scheme.

I’ve delved into the items I saved from Mum and Dad’s after they died in 2021 to discover more about Mum’s evacuee years. Here’s what I found.

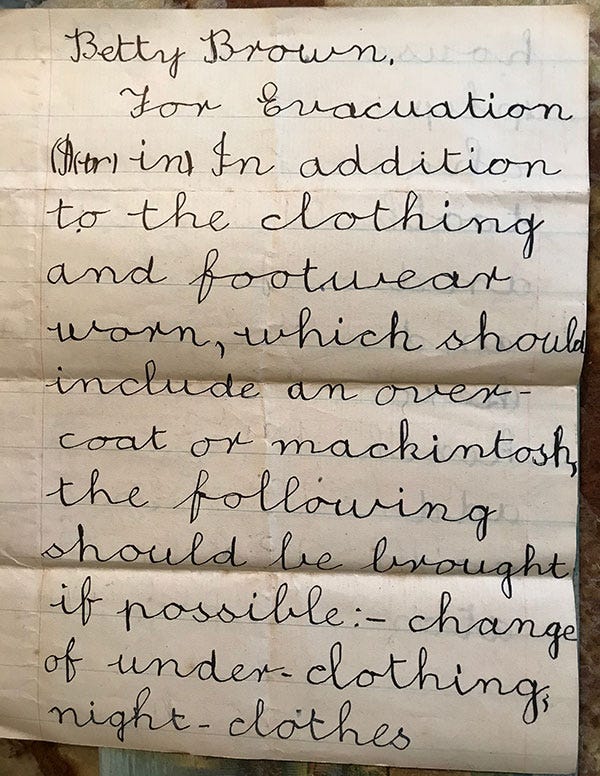

The packing list

Mum copied out the items to pack in her tiny suitcase, including house-shoes, plimsolls, a change of socks, toothbrush, brush and comb, towel and soap, handkerchiefs, stamped addressed postcard and respirator (gas mask).

“Thank you for the pretty dresses”

Mum’s aunt, Ada Jefferies, was a seamstress. She made the matching dresses (pictured top) mentioned in this undated letter from Mum’s and Jean’s first foster family, the Sawers.

Tawelan, Newtown, North Wales

Dear Mrs Jefferies,

Thank you so much for the pretty dresses you have sent the children. They are delighted with them and the slips will be so useful. Betty’s dress fits perfectly. Jean’s is just a little wide on the shoulder, but my daughter can easily alter that.

I would like the children to have new coats for winter – they look so nice when they are dressed alike. The other coats will do for school but they are rather shabby for Sunday. Don’t you think navy blue would be nice for them? Still you will know what you can get.

Glad to know you have had a holiday. We have been to Bath for a few days and the children are looking so well – they were bathing.

We have not had any raids here, but the German planes pass over and dispose of bombs a few miles away but did not do any damage. We do not have to get up at night-time – it must be very trying for you.

Thank you for the money for stamps.

The children send love and kisses.

Your sincerely

Nora (?) Sawers

“We were very lucky, we went to lovely homes”

My son, Milo, interviewed my Mum about her wartime experiences, when he was at primary school in 2010. This is what she told him:

Dad worked with the air ministry, and in his spare time was a civil defence worker. He monitored where incendiary bombs might fall and made sure they had buckets of sand to put on quickly if they fell. Mum did some nursing and helped to run the first aid station.

My older sister, Dorothy, was working age and she joined the WRNS (Women’s Royal Naval Service).

When Jean and I were evacuated, nobody knew which town they were going to. We were very lucky, we went to lovely homes.

Bombers were coming to Liverpool docks to try to sink ships in the River Mersey.

At first when we were evacuated they called it the ‘phoney war’ because there was little fighting during the first few months. When the summer holiday came round in 1940 parents brought their children back to Birkenhead.

One Tuesday Jean and I were taken to New Brighton, a seaside town nearby. By the rocky tower were rides for children, but because of the war they were closed.

Another mum asked them to open the rides for us. Then there was an air raid warning. We gathered together and went down the rock steps of the tower. After the all clear we came up the steps into the fresh air.

All round where we’d been, shells had burst and there was shrapnel right up to the doors of the tower. Some of the rides were ruined. If we’d been out there we would have been injured, or worse.

We had to wait until Saturday for a train back to Wales. Jean and I slept at the top of the cellar stairs in the house and heard German bombers coming over. There was a shelter in the street, but it was not all that safe. Some buildings nearby were destroyed.

I just had that four days’ experience of the bombing, then went back to Wales.

The Christmas gift

Betty and Jean made this kettle holder for their mother one Christmas while they were away. I found it stored in a chocolate box with the gift label still attached.

Education

Mum thrived at Newtown County School for Girls. She loved history, music and drama. She took the role of Portia in The Merchant of Venice in the school play.

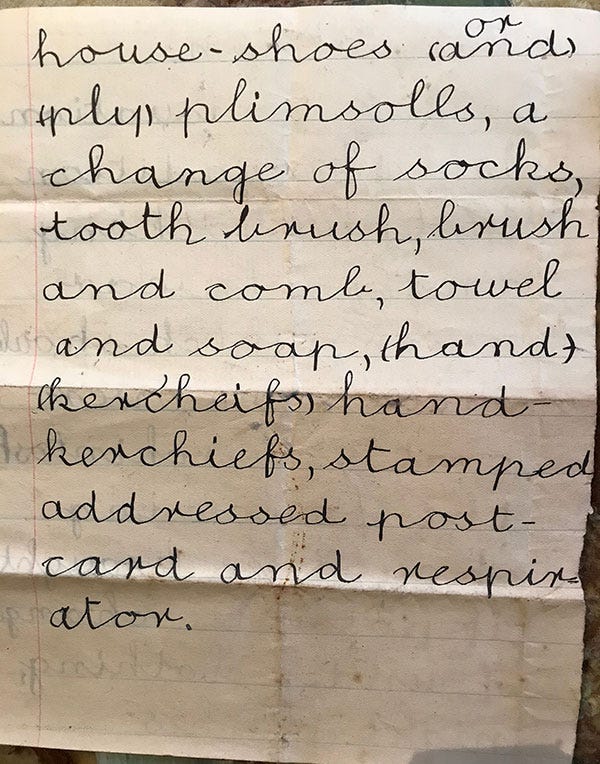

Here’s an excerpt from her Needlework book in 1943 (age 12), with miniature sewing samples. She got a B+ for her work on pleats. Projects included making aprons, bodices and knickers.

Memories of Wales

By Betty Varley (written in a notebook in 1985)

There passed four eventful and mainly very happy years – the Severn flooded or serene, spring lambs and primroses and later, the joy of helping to feed a new calf, and milking its mother; and throughout, the happiness of a growing understanding of dogs.

On my thirteenth birthday I was riding a friend’s pony – I was last to try and there was no saddle. Someone gave it a hefty whack, and I ended up unconscious! Soon afterwards we went home on holiday – and our parents kept us at home; we often regretted this.

I had special regrets, for I contracted rheumatic fever a few months later, and this was to affect my entire life1.

Going home, Summer 1943

Mum was dismayed to find that she would not be returning to Wales after the summer holiday of 1943. There had been no opportunity to say goodbye to school friends or to her foster families. The Woollies wrote this letter to Mum and Jean that summer (punctuation amended, for sense).

Brown-wen

Llanidloes Road

Newtown

N WalesDear Betty and Jean

I received your welcome letter quite safely and glad you are having a good time at home. Two letters came for you so I am addressing them and sending them on. I am going to Leicester next Monday for fortnight so I hope the weather will be fine like it is now. We were busy last week getting the hay in from the field in the Park Lane. I saw Sybil and Topsy climbing over hedge to go down to the river for a bathe last Friday, I asked them if that was the way you all went to the river. Uncle Fred is missing Jean this week at night when he goes to do the cattle, he say it very lonely now doing it all by himself. The cat miss you both, for a day or two she kept looking round on the settee to see if you were both coming for meals. I don’t think she could make it out. Now she come on my chair to see if she can get anything to eat. Well Jean, Betty wrote so I am looking out for a letter from you. Will close now, have a good time now you are at home.

Love from Auntie Annie and Uncle Fred

Mum spoke to me and her grandchildren frequently about her evacuee years. A favourite theme she returned to was of how she loved to play her 3/4 size violin. She maintained it was a Stradivarius2 and I wondered whether that was wishful thinking in her old age. But my hunt through her papers turned up this moving account, written in 1987, when mum was 57:

The broken Stradivarius by Betty Varley

26 December 1987 (written in a notepad)

I’m thinking of the days when I’d hurry home from school, along the country road to the farmhouse where we stayed, change quickly, and taking my violin from its case, would tune it, and lift it lovingly to tuck under my chin – and stroke the strings into music. The body reverberated with melody. The sweetness of tone delighted, coaxing more exploration through page after page of my music books. Then I’d try other melodies I loved, playing by ear.

The fields stretched away to the green hills; birds sang in the hedgerows; and I was part of the creation of lovely sounds.

I could not know then that the instrument which brought me such delight was a rare thing. Battered its case was indeed; and a deep scar marked the polished beauty of the instrument itself; but it sang with such beauty of tone that a vision of heaven came into my room whenever I played: my inexperienced hands could not do it justice; but it gave lovingly whenever I asked, inspiring me to more and more melodies of Mozart and Mendelssohn across the summer meadows.

Polishing it carefully, I noticed, looking closely through the decorative sound holes, that there was a dusty label inside. In a certain light it was possible to read: “Antonio Stradivari Cremonensis AD17?1”

I had no idea what this signified – except that it was old. The exact date was difficult to decipher. I supposed that all violins had these labels inside.

I played each day with joy and satisfaction. Orchestral practices began, and I kept up as best I could; some girls were much more experienced, some were beginners like me. Their violins were mostly full sized, unlike my beloved “three-quarter”. That was one advantage in being small! Somehow theirs sounded harsher, less melodious.

We went home – for a holiday, they said; but our parents decided to keep us at home, as the war no longer threatened Britain’s cities. I grieved for my violin, thinking that I would not see it again; but one day our big suitcases arrived – and there, strapped to the top, was my beloved violin! Joyfully I took it up to my bedroom in the top of the house; no fields now, but rooftops marched away into the distance, where the shipyard’s cranes stood to attention beside the grey river; and across to the left, the trees peeped over the housetops as the Park reached up the hillside to more houses and the Hospital.

I opened the case, tuned up, and began to play… awkwardly at first, but then the sweetness began to flow through into the melody, and the glory of my little Stradivari lit the room.

For a few months my happiness knew no bounds as I mastered more and more of my music books. Then illness struck; and for nearly a year I was out of action, able after a while to return to school, but with activity limited.

Then at last, I began again to play; it was difficult, after such a break; but I realised that there was another problem: I was growing out of my little “three quarter”.

Some time later, my parents decided to let me have lessons again – and a full-sized violin was found. Expectantly, I took the instrument and tried it out. The sound was dull. I was out of practice, of course. Weeks of work didn’t seem to improve things; the magic had gone. I sought out my old favourite… and discovered that the sweetness was sure as ever, but my lengthened arms were awkward.

The new violin had no case, so I’d transferred the instrument into the small case – a neat fit, but it just went in. I wrapped the little instrument in stiff brown paper and stood it up carefully on top of some special books; and there it stayed for years.

Eventually, I married and went away. One day, I heard that my parents were about to move. I wanted to go and help, but being in poor health, and expecting our first baby, I was advised to stay away.

Long afterwards, searching in vain in my parents’ new house, I asked and was told that vandals had broken in during the move and many things had been ruined, including my beloved violin. Just a couple of pieces remained. Never would my children, nor my grandchildren hold this magic. I grieve still for the beauty that is no more.

Looking up the history of Stradivarius violins, there were copies made, so I have no way of knowing whether Mum’s was an original or not. She believed it was and she mourned its loss throughout her life. Perhaps it’s no surprise that, after leaving home with so little and relying on the kindness of strangers for the next four years, the possessions she had as an evacuee were so treasured.

Being evacuees left a legacy for both sisters. Mum was a hoarder (though she never used that word herself), and I wonder whether her wartime experiences contributed to her inability to part with things. But then, my Aunty Jean, who had been uprooted at an even younger age, was the opposite: efficient and minimalist, she hated clutter. She had a long career as a senior secretary in the Civil Service.

Jean, though, who had lived away from her parents between the formative ages of four and eight, found it particularly difficult to reconnect with her mother when she returned home. The scars were lasting.

Returning to Newtown

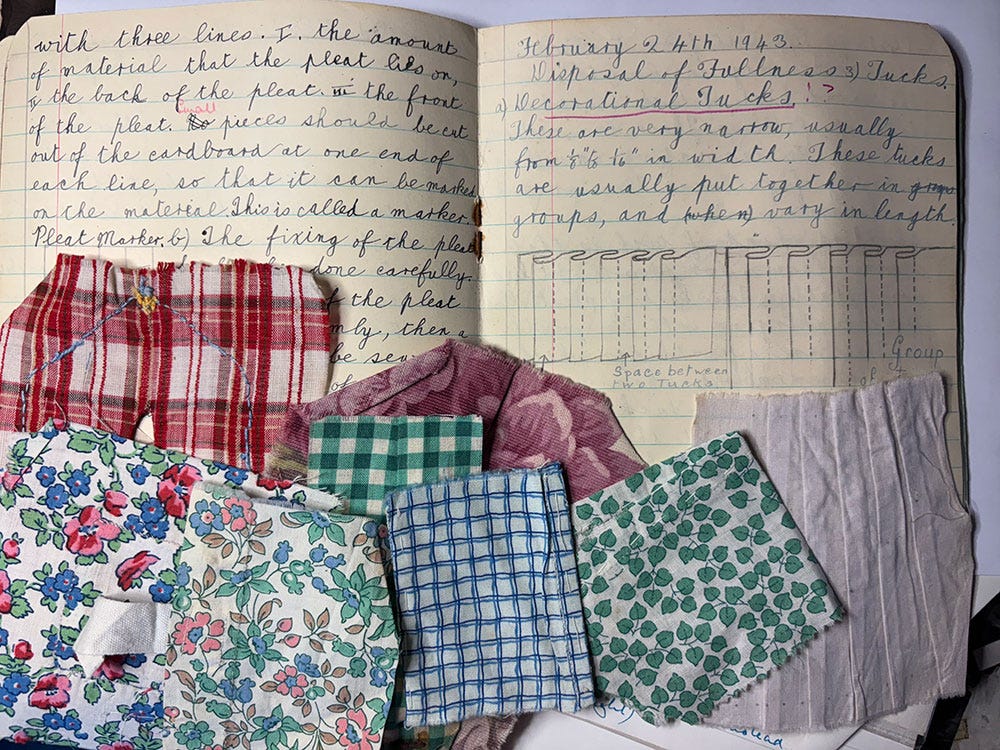

Mum kept in touch with her Newtown foster families for many years afterwards. She and Dad visited them while on holiday in Wales in 1962, with me and my brother in tow.

A surprise poem

Finally, a poem about Jean and Betty in Newtown, by Mr Tom Beaumont, a mechanic. It was found by the wife of Mr Beaumont’s grandson, who passed it on to Mum in 2015 (after Mum had been in touch with the Newtown local history group3):

Of two little evacuees

The younger is rather a tease

The elder is staider

In homework a wader

With hopes of early degrees

I was inspired to research and write this piece after reading

’s The One, about a special violin of her own.Over to you: have there been long separations in your own family history – what impact did it have? Did you have a favourite musical instrument? I love to hear your feedback and always reply to comments.

Thank you…

To everyone who read last week’s piece, On failing to get into The Royal Ballet School, and shared it or left comments. Clicking the heart, sharing and/or commenting below all helps other people find my work.

If you’ve enjoyed reading and aren’t already subscribing, please do join up so you receive my work regularly. Nothing on Wendy’s World is behind a paywall. I really appreciate some of you opting for a paid subscription to support my writing, or popping something in the tip jar. Free or paid, though, I’m delighted to share my writing with you!

Until next time!

© Wendy Varley 2025

Rheumatic fever left mum with weak heart valves, which affected her energy levels and ability to work.

Antonio Stradivari, 1644–1737, world famous Italian luthier (violin maker).

After publishing this piece, Newtown Local History Group kindly reproduced it in the Spring 2025 edition of its quarterly printed journal, The Newtonian. Mum would have been delighted to know that her story has been shared with the town in this way.

Love this so much! The pictures, the letters, the packing list, even reading your own mother’s words about her violin. There is so much life in this post! Thank you for sharing with us 💛

My neighbour, Julia, is 92 and explains that she and her brother didn't grow fond of their parents ever after their return home but remain close still now to the children of the family they were evacuated to. It's hard to imagine such separations being the norm yet just recently I found a pile of aerogrammes sent between my mother at school in England and her mother in Shanghai, spanning several years.

Great work Wendy. Proper memoir. Fabulous.