As a child, I was lean as a fox, eating when hungry, stopping when full. Dessert was a fifth of a sliced-up Mars bar. But once I finished dance training, my first thought was: “I’ll have to watch my figure now” and my relationship with food changed.

25 March 1976 diary entry, aged 15:

“I’m depressed. I’ve just been reading Gone With The Wind. I sympathise with Scarlett. She’s feeling a bit like me at the moment, but has more reason for it. I wish my slimming would hurry up! I’ve lost half a stone, but there’s plenty more where that came from.”

Let’s just pause there for a moment. Am I really comparing Scarlett O’Hara in Margaret Mitchell’s epic novel, trying to save her family home during the American Civil War with me, a schoolgirl in South Yorkshire, trying to lose a few pounds?

Perhaps it was less the war traumas and more her being laced into a corset that I was thinking of, convinced that she was “fat” if she couldn’t get her waist to measure 17 inches, the smallest in three counties.

My diary was full of calorie counting and food chat, such as:

“Dinner was pork today. I ate around 1200 calories, not really too much, but I’m going to try to survive on half a pint of milk tomorrow, all the same.

“I’ve been watching Romeo and Juliet ballet on the telly. It was in the Bolshoi Theatre. I now weigh 8 ½ stones. I did lots more skipping, hip walks and pull-ups today. My complexion seems to look better for my reformed eating habits.”

and:

“It’s cold outside and I’m sitting right by the window upstairs in a draught, but I couldn’t care, I don’t mind catching cold. I wouldn’t mind having flu for that matter, it makes me lose my appetite anyway.”

The shame of bingeing was so acute that I rarely mentioned it in my diary, but I remember. The first time was when I brought home a fruit loaf I’d made in Cookery class and ate the entire thing, before anyone knew it was there. I felt ill but couldn’t make myself sick, and I despised myself.

My weight yo-yoed. I was not overweight for my eventual height of 5ft 6ins and, looking back, I can’t believe I panicked if the scales tipped over 9st.

The obsession increased during adolescence while my body naturally filled out and my self-confidence waned.

My New Year Resolutions, 1st January 1979 were:

• Let’s have another good diet

• Get good A-level grades

• Be happy, individual, myself and have a good year

A revelation

In September 1979 I took a gap year, leaving home to be a Community Service Volunteer in a psychiatric hospital in Surrey, living in the nurses’ home. The work was intense. So was my suddenly hectic social life, making friends with the other volunteers. I was unsure how to handle myself. I was bingeing a lot, struggling to do up my jeans and, for the first time, had rolls of fat over my waistband.

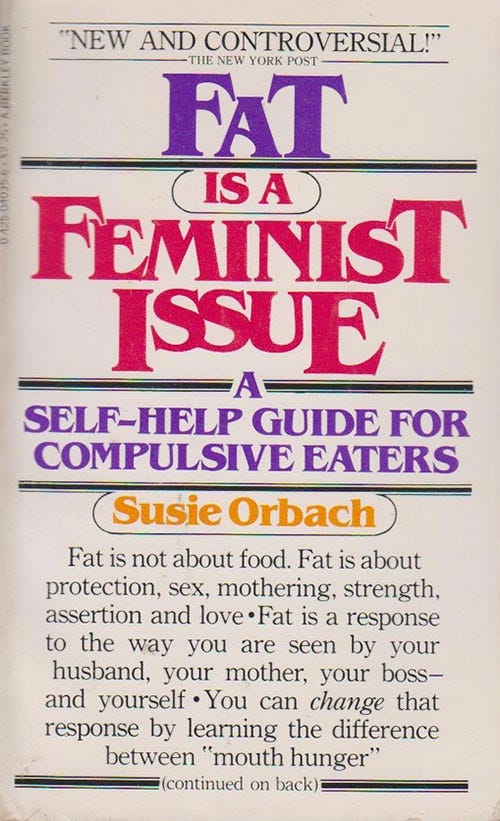

Then I read the book Fat Is A Feminist Issue by Susie Orbach (published 1978). It was a revelation.

One of the first exercises in the book is: “Imagine yourself in a social situation […] Now imagine yourself getting fatter, in the same social situation…” and then think about how that makes you feel: what is fat you saying to the world? (I’m paraphrasing, for brevity.)

I realised, just from that introductory exercise, that I was using it as a barrier, to protect myself from feelings about my past and to protect myself from other people. Orbach writes:

“As this function becomes more apparent it is possible to be more generous to yourself, to regard the compulsive eating and the attempt to get fat as a way in which you have handled particularly difficult situations. The compulsive eating can then be looked on as an attempt to adapt to a set of circumstances rather than as irrational, ‘crazy’ behaviour.”

In Chapter 2 there’s a similar exercise, but imagining yourself thin. Many of the case studies included in the book resonated. Revisiting the book now, I’m struck all over again by how much sense it makes.

My parents had frequently argued about food. Dad had come from a family where women catered for their men. His mother took pride in her cooking. My mother could never get the timings right. Despite owning a copy of Mrs Beeton’s Book of Household Management, she struggled to serve up appetising meals, frequently burning the dinner. I couldn’t bear their arguments and, as a natural peacemaker (middle child syndrome), I took over cooking the Sunday lunch at age 12, plus any other meals that I was around for, when I wasn’t dancing. My younger sister helped, too. I learned early to be an appeaser and a provider.

My mother could be faddy about food. She’d call Battenburg cake “energy cake” (no surprise given its whopping sugar content!) and boast that she’d stayed up all night doing paperwork after eating it. She was ultra self-conscious about her protruding “tummy”: a hernia caused by having us three children by Caesarean section in the days when the incision was vertical. Her abdominal muscles hadn’t knitted back together. She always wore a girdle.

There was my dream of having a sylph-like ballet body, which of course was not going to happen once I stopped dancing every day.

Emotionally, I was a mess, and didn’t know what I wanted from relationships. I had no problem attracting men, and although I wanted to be noticed, I also resented it. There’d be times when I’d gain weight, cut all my hair off and think: Ha! Still want me now?! Then realise it didn’t put men off. (Nope, this wasn’t my passport photo, I just needed to vent my frustration.)

Fat Is A Feminist Issue helped me unpick what was going on psychologically. Eating was filling an emotional void in my life. It had nothing to do with hunger.

But of course, theory is one thing, practice is another and it took several more years before I broke the binge/starve cycle and re-found my “normal” appetite for food.

It happened gradually. Once I started working, I was too busy to worry. By the time I started in journalism in 1983, I felt I was on the right path and was genuinely happy in my job. Soon after that, I ended a destructive relationship which I’d fallen into aged 20 at my lowest ebb and was still stuck in four years later.

Meeting Ian in 1986, having our daughters so soon after, there was simply no time to fret about food or body image any more. I think when we met I weighed around 11st but was no longer obsessing over it. I felt loved and accepted by Ian. And carrying triplets, I developed newfound respect for my body as it did its own thing. All those hormones sloshing around plunged me into extreme pregnancy sickness during the early weeks, then I expanded so rapidly that I thought we would run out of tape when my waist was measured to check the babies were growing well. It was an extreme way to find out how it felt to take up space.

I rediscovered what it was like to eat to live, rather than living to eat. The desire to binge had faded. So had the desire to diet.

I didn’t want to pass on body hang-ups to my children and tried to be matter-of-fact, even during their own fussy years, when all they wanted was pasta and cheese.

My focus now is on staying fit. Sugar and ultra-processed foods affect my mood and my health, so I avoid them. The introduction to the latest edition of Fat Is A Feminist Issue acknowledges that the first edition skipped some basics about nutrition.

I know that I’m not unusual. So many people have or have had hang-ups about food and about their bodies. I have male friends who took slimness for granted in their youth, now struggling with food and body issues in middle age, as the threat of Diabetes looms. And I know that for some people, the cycle of disordered eating can last for many years, or a whole lifetime. I’m lucky that I managed to “re-set” in my mid-twenties, and a lot of that is down to having read Susie Orbach’s book when I needed it most.

Over to you: have there been times in your life when food and body image have dominated your thoughts? What, if anything, has worked to break the pattern? I value your comments.

I was inspired to write this after being a long-time fan of

’s Substack, The Next Write Thing. She is open about her ongoing recovery from disordered eating. For example:Thanks to everyone who responded to last week’s piece, about my mum’s time as an evacuee during WWII. Your comments were so touching, with vivid stories of families affected by war and by separation.

Clicking the heart and/or sharing this piece will help other people find my writing.

Thanks for reading, and if you haven’t already subscribed, I do hope you will!

Or, if you wish, there is a Wendy’s World tip jar:

Until next time!

© Wendy Varley 2025

Issues with food in adolescence? Hang ups about being chubby? Goodness me! I had hangups enough to make jam with them! In all fairness to myself, I think I never was more than 10 pounds too big, but the struggle to lose them, the unconquerable compulsion to eat, especially sweet stuff... the constant "observations" of stupid aunts commenting that if I did not lose weight I was going to end up looking like a "madame" (as in the woman in charge of a brothel), that my hair was too long, too curly... and definitely, although my legs would never be like my mother's, they would certainly look better if I lose weight... So my early twenties saw me going to my GP and asking for slimming pills... some concoction that suppressed my appetite and kept me going for a wee... but hey! I was happy. Did they contain any degree of anphetamine? No matter. I would rather be hyperactive and slim than fat and depressed... Was I using food to replace an absence of love in every form? You bet! So I sympathise no end with you and all those teenagers -especially teenagers- who are using food as a substitute for love. Having said that, I deplore the idea of indulging just because "we all look different and that is fine". Of course we are. Of course it is fine, but there is another much more important issue than just looks, and it is HEALTH. Over feeding children is as criminal as starving them, but I digress. I rest my case, though

My story - written by Wendy. xxx