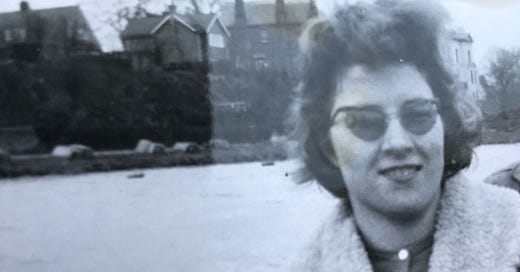

The Lost Voice

A devastating stroke robbed my aunt of her speech and mobility. Reading aloud to her kept us connected.

I got a call from the police in October 2018 to say that my 83-year old Aunty Jean was in an ambulance being taken to Bournemouth Hospital. Please could I go there urgently? I was listed as her emergency contact. The policeman wasn’t sure whether she’d survive the night. She had been found collapsed in her flat, a suspected stroke. He didn’t know how long she had been lying there.

I made a dash for the last car ferry from the Isle of Wight, then drove along the south coast to Bournemouth.

The last time I’d seen Aunty Jean was at my daughter, Becky’s, wedding two months earlier. Becky and her husband had wanted their celebration at our house. When she heard of their plans, Jean tutted at the unkempt state of our garden and offered to help redesign and plant up the courtyard, so that it was presentable for an outdoor party. She maintained the communal garden at her block of flats and had volunteered at stately homes, keeping formal flower beds looking pristine, so she knew her stuff.

She chose perennial plants, thoughtfully dedicated to family members. Agapanthus for my brother and sister-in-law, who have South African connections. Giant daisies for my mum, because there had been daisies in the garden in Wales when Mum and Jean were there as child evacuees during World War II. Cheerful rich orange Helenium Moerheim Beauty for me, because she thought I had a lovely smile. Red hot pokers for Ian and our son, Milo, as she thought of them as “warm and spiky”!

Jean and I both watched Gardener’s World that summer and exchanged messages about what we’d liked in each week’s show. A reluctant gardener up to that point, I realised that anyone could have green fingers with an Aunty Jean to teach them.

She thought of herself as bionic after having two titanium heart valves fitted in her early seventies, but apart from that, she’d stayed fit, active and independent since her retirement from her job as a senior secretary in the Civil Service. Ian and I joked that she could have been a spy as she’d signed the Official Secrets Act and habitually only dispensed information on a “need to know” basis. Discreet to the max.

She had lots of friends, a playful sense of humour and was a pillar of her local community, volunteering her excellent secretarial skills to a succession of charities. She’d just taken up tai chi, kept herself trim and ate healthily.

She was divorced. Her only child from that marriage, Alison, had been born prematurely in 1969 and lived just a few hours. She never got to see or hold her. I remember my mum’s sadness for her sister, and my own at not having a new cousin after all. Aunty Jean opened up to me about it just once, after my son Otto was stillborn at term in 2000. “Of course, I wanted to replace what I’d lost, but R– [her ex-husband] didn’t want to put me through any more pain.” She had handed in her notice, in anticipation of full-time motherhood, but following Alison’s death, returned to work and took up where she left off.

Mum and Jean had been estranged for many years (Jean’s choice). I put some of Jean’s reticence down to her separation from her own parents during the war. She was only four when she and mum went away to Wales. She kept her divorce hidden from me and the rest of the family for several years.

I gradually coaxed her back into the fold. She agreed to join us for a family gathering on New Year’s Eve 2010, the first time she and mum had seen each other in decades. They danced together to Bad Romance by Lady Gaga, a glorious sight.

Jean was pragmatic. “When I ‘pop off’, here’s where you’ll find my Will and important papers,” she told me. She gave me a spare key to her flat and told me the name of her solicitor and her preferred undertaker.

Neither of us knew that rather than “popping off”, she’d be left incapacitated, unable to speak or move following a devastating stroke, and would lie undiscovered for three days. In a cruel twist of fate, neighbours who had noticed that she wasn’t out in the garden as usual, and friends who wondered why she hadn’t shown up in town for their regular Saturday coffee date, all thought that perhaps she had come to visit me on the Isle of Wight, so had delayed alerting emergency services. (She’d been due to visit me the following week.)

When I arrived at Bournemouth Hospital, Jean was alive (just), immobile and mute, hooked up to drips, bearing a head wound from where she’d hit her bedside table as she collapsed. When she eventually opened her eyes, she looked at me blearily but I thought with recognition, and I could only guess what she was thinking. I was told that it was still touch and go. Against the odds, she clung on to life.

I spent the first night in a hotel, the next at her flat. Her bedroom, where she’d lain on the floor for three days, resembled a crime scene. I took the Stanley knife from Jean’s toolkit and carved out and disposed of a big chunk of carpet and underlay. I slept in the lounge.

It was a task to find clothes suitable for her to wear in hospital. She took pride in her appearance – her wardrobe was full of Jaeger, cashmere and Country Casuals (which are actually very smart) – and she only dressed down when gardening.

I found in her pile of post a parcel of two books by Robert Macfarlane: The Wild Places and The Old Ways, which I knew she must have intended to read. During the hours spent sitting at Jean’s bedside, I started reading her The Wild Places, about Macfarlane’s journey around Britain and Ireland exploring areas that are still given over to wilderness. It mentioned places I knew she’d visited. There was her wartime connection with Wales, of course, and she’d spent many holidays exploring rural Scotland.

It was by reading Robert Macfarlane’s book aloud that I knew for sure that Jean understood me, even though she could not speak.

The first sign was when I got to a passage on page 34 about the author bird-watching at Ynys Enlli, an island off the north Wales coast. Jean nodded very deliberately four times. It was the first time she had attempted to communicate. I re-read the bit where she’d nodded, to fully take in its significance. The sentence was:

“I lay in the quiet dark, watching the light beams turning silently above me, until I slipped back into sleep.”

I felt sure she was remembering those three days when she had drifted in and out of consciousness, waiting to be discovered or to die. Perhaps she was wishing she had died.

A few minutes later, the nurse took Jean’s blood pressure and Jean deliberately held her breath. “Are you still there? Breathe, Jean!” the nurse reminded her.

Jean was locked in and she knew it. And I was suddenly responsible for her but had no Lasting Power of Attorney to legally act on her behalf. My mother was technically her next of kin, but 250 miles away in Yorkshire and increasingly frail herself. I was the closest family member geographically.

Without Power of Attorney, I had to apply to become Jean’s Legal Guardian, a process which took ten months, during which all of her finances and accounts were frozen. The bureaucracy of it dominated my life.

When I looked back at old emails from her, I realised that Jean had suggested granting me Lasting Power of Attorney back in 2011. It had seemed so non-urgent at the time that we didn’t follow it up.1

She remained in the hospital’s stroke unit for three months. Although she got stronger, there was no clear improvement to either her speech or mobility. Following a stroke, swift intervention can make all the difference to recovery. She had missed that window by a long way. Her right side was entirely paralysed. Any attempts to weight-bear on her left side were so painful that she couldn’t endure it.

Jean needed 24-hour nursing care: hoists to move her, assistance with eating, continence care.

I travelled to Bournemouth to visit Jean every few days, juggling it with work and family commitments.

Once she was stable enough to leave hospital, I arranged for Jean to move to a nursing home near me. The local Speech and Language Team agreed to see her and lent me a toolkit of word cards and everyday items, to test Jean’s comprehension and to try to decipher what she might want.

I took items out of the box one at a time to show her. When I brought out an envelope, she nodded. Aha! I found her address book and showed her names. She nodded when I got to the name of her ex-husband. “Do you want me to let him know you’re here in this nursing home and what’s happened?” I asked. She nodded. In fact, I had told him about Jean’s stroke right at the start and I was able to show Jean the cards from him that I’d read to her weeks before, but which she’d been too fuzzy to recall.

I had finished reading The Wild Places to Jean and was well into The Old Ways (about Britain’s ancient paths) when Covid hit in 2020. The double whammy of nursing homes being physically locked down while Jean was unable to communicate was gruelling. When the staff set up a phone call or video call, it could only be one-sided. I would tell Jean family news and anything else I thought might interest her and hope that my voice meant something.

Jean caught Covid in June, along with many of the other residents, and although she recovered, her appetite waned. By the time garden visits were allowed and I could once again sit with her outdoors and resume reading The Old Ways, she was tiny and frail and refusing to eat.

Jean died in August 2020, nearly two years after her stroke. I was so sad that my lively, clever, stoical, determined aunt, who had come through those early childhood challenges and made a success of her life, faced such hardship at the end.

We were allowed thirty people at the funeral, and many more of her friends watched the service from the crematorium online. One of the privileges of that time was finding out how much Jean had meant to so many people. One of her mottos in life and in her work had been to “give people more than they expect”, and she had always done that.

I am grateful to Robert Macfarlane for the two books that made that time more bearable for both of us. They spoke to Jean’s love of nature, and of Britain’s landscapes that she had so enjoyed. They helped us to communicate, even though Jean could no longer speak.

A testament to the power of reading aloud.

© Wendy Varley 2025

Please do comment below if you’re able. I love to read your feedback. On the therapeutic effects of reading aloud, or of tending gardens? Suddenly having to arrange care for a relative? The importance of Power of Attorney?

Thanks so much to all who engaged so warmly with last week’s piece, Hot Pants and Modesty Flannels. Glad it raised smiles and a few eyebrows!

I’ve since sorted out Lasting Power of Attorney for myself, so if anything happens to me, my family knows they can act for me. Think about it long before you need it, is my advice. In the UK, all the information is on the government’s (gov.uk) website.

This is such a tender tribute to your aunt. Being locked inside her body after her stroke must have been devastating but what wonderful books to read to her and perhaps bring a sense of freedom to those difficult days.

Wow. This is very truthfully and beautifully written.

Reading aloud is such an amazing thing and I think it can be very healing.

Your aunt sounds like she was a very brilliant and interesting person! 💛