The InterBet

No-one could disseminate family, local or world news faster than my mum, Betty, sitting by her landline phone.

I’ve had the house to myself this week. A rarity. Ian’s away and our adult children are off feathering their own nests. They flit in from time-to-time for a brief visit and flit off again. This week it’s been just me and the dog and Storm Bert bringing us wind and rain.

While he’s travelling, I’ve taken Ian’s place visiting his mum, J, who’s in a nursing home and has dementia.

J was a rock when the children were little. Eight years younger than my mother, fitter, more organised, and closer geographically, it was her I phoned when my triplet daughters were three months old and I was physically, mentally and emotionally exhausted.

Ian was working long hours as a magazine journalist. There was no paternity leave and he’d used up all his holiday allowance when we first brought the babies home from hospital.

I was squeezing in freelance writing during the precious minutes that my daughters slept simultaneously.

I asked his mum whether she would come for a few days to help. She sensed the alarm bells and didn’t hesitate. She cancelled her plans and showed up, smiling, efficient, capable.

She remembers it, too. (Or she did a few weeks ago. What she remembers shifts from day to day.)

Visiting J in the nursing home this week, encouraging her to conjure happier times through reminiscence, has made me crave my own mother’s voice. I wanted to find the answerphone light flashing when I got in, as it used to pretty much every day when she was alive. My mum, Betty, was one of the few people who still rang the landline. I wish I still had her last message, which of course I deleted, not knowing it was the last.

We called mum The InterBet, because of the speed with which she could disseminate family, local, or world news sitting by her landline phone.

“Don’t tell mum this yet…” became a bit of a joke between me and my siblings. We knew that if she got wind of a job interview, an engagement, an illness, a pregnancy, a break-up, a new love affair, or any tasty bit of trivia, the rest of the extended family would be brought up to speed by phone within the day. So would any other friends who called and anyone she met at the shops.

Often she’d ring and say, “How’s you doing, Bemby?” (I’ve no idea why she still used my baby name when I was a fully-grown woman, but it was a habit she never broke.) “Is everyone alright? I had a feeling that something is wrong somewhere.”

“Mum, there is always something wrong, somewhere,” I’d say.

Whatever peril popped up on the news, she would do a mental geolocation of her children to gauge our proximity to the disaster zone.

In the early 1980s when I was commuting into London, she was constantly worried about the IRA, and would phone me at work. “I saw on the lunchtime news there’s been a bomb scare. Just making sure you’re safe.”

Or the phone would be ringing as I walked through the door of my flat. “It said on the radio that Charing Cross station was shut. Just wanted to check you got home alright.”

In old age, when they were more or less housebound, she and dad rewired the phone so they could have his and hers handsets and listen to our news simultaneously. “We’re both on now,” they’d say. Then I’d ask dad a question and mum would interrupt his answer within five seconds.

For mum’s 80th birthday in 2010, we had a party at the local community centre she’d helped to found and made her a printed family photo album, so she’d have memories of her children and grandchildren to hand.

Her 90th took place during the pandemic and only my sister could visit. Her eyesight was failing, so there was no point making her an updated album.

My sister suggested making her a compilation of voice recordings from everyone in the family, sharing their fondest memories of her, so that she could play it back at the touch of a button.

Thanks to that audio file, I can still listen to both my parents’ voices, as we included a recording of mum, too. She recalled how she nearly drowned in the Mersey when she was two years old, strolling with her mother and older sister towards the training ship moored in the river. Saying the ship’s name, “Indefatigable”, was her party piece.

She walked into the water, thinking it would be like the shallow rock pools she’d dabbled in at the beach. My frantic grandmother pulled her out by her mop of curly hair, which was floating on the surface like seaweed.

My dad remembered meeting mum for the first time on the dance floor at Pwllheli Butlins holiday camp in 1954 and how he knew as soon as he saw her that she was the girl for him. He pushed for a speedy wedding, as they were taking it in turns to travel across the Pennines at weekends to visit each other and he was missing weekend maintenance shifts at the pit, where he repaired machinery.

On the morning of their February wedding, they awoke to two inches of snow in Yorkshire and had to get to Birkenhead by 1pm by bus, train, steam train and ferry. Everything ran like clockwork and they made it to the church on time.

Mum’s eight grandchildren all spoke of her love of animals and nature.

One of my nephews recalled her trip to South Africa to visit when he was 11:

“You were working in the garden on a nice sunny day. To my horror, I saw a massive venomous baboon spider on your back and I was panicking a little bit.

“I told you, ‘Nana, there’s a big spider on your back.’

“I remember that you weren’t concerned about yourself at all, you were concerned about not harming the spider.”

Another recounted the time she was visiting us and our cat caught a vole.

“The vole was a bit injured and had an open wound that you were keen to heal up.

“You got the Superglue out, and in trying to nurse this vole back to health and close up the wound, you accidentally glued it to your hand instead.

“It’s representative of the efforts you’d go to to look after smaller creatures.”

One of my nephews lived with my mum and dad for a couple of years as an adult and recalled the deep conversations they’d have after watching Brian Cox’s TV series about the stars and planets.

“Always fascinating to hear yours and grandad’s insights about life in the deep conversations we would have afterwards.”

My sister’s oldest son said:

“I remember your stories that I couldn’t get enough of. Stories of you visiting your friends in America. Minneapolis, Duluth. Badgers tearing through undergrowth. A wolf lolloping across a road.

“Those were the first stories I was ever told that showed me in words, in voice, experiences that I could not get on TV or through my parents or through visiting places myself.”

My daughter, Olivia, recalled mum holding hands and dancing with her whenever The Archers theme tune came on Radio 4. (She was a loyal fan of the programme.)

Her triplet sister, Alex, said,

“Aged seven I helped you hold a hedgehog called Henrietta. I distinctly remember the feel of Henrietta’s spines in my palm.

“We peered at tadpoles in the small wilderness in the garden and I saw some were growing legs. Conversations about evolution followed.

“You showed me how to crack slate to look for fossils of Prehistoric animals.”

Ian recounted meeting my mum for the first time:

“I remember when we first met, Wendy and I drove down to your gate and you emerged from the shrubbery with a big smile and some bits of the garden still tangled in your hair.

“Wendy had a go at pulling the stalks and leaves out of your hair, but the truth is it fitted so well with your nature, in touch with wildlife and a very colourful person.

“We went inside the house, which was bursting with everything you’d collected in every corner and pushing back from behind every reluctantly-opening door. So many things. As if they’d been deposited by the tide going out in concentric rings from the Aga and into the house.

“All those bits and pieces were baffling to us, but they all anchor your memories in time and place.”

My brother talked about the freedom mum had given him to explore: “No tabs, just go and find things out for yourself.”

My sister and I acknowledged the creative opportunities she’d given us, sharing with us her enthusiasm for music, drama and the arts, always encouraging us to have a go.

My daughter, Becky’s, voice message was a short poem she wrote, which she also read at mum’s funeral in 2021:

Things My Grandmother Taught Me by Becky Varley-Winter

Desire is like a beautiful horse, you have to look after it carefully

Even a lame pigeon needs rescuing

Many can fit inside a small car1

Determination is the source of invention

Don’t waste anything

All strangers are fascinating

Weeds are under-rated

Why should Mary be ever virgin?

Roses can grow through open windows

Be wary of escalators, you can’t trust them

Everything has a soul

There is no limitation on life

No matter what happens you must believe the universe is good

Forget the bad things

Don’t bear grudges

Keep going

Be indefatigable

Feed the birds and mice

Be a character of light

It was poignant listening to all those voice messages again, and especially to hear Ian’s mum, J. Four years ago J was in good health, articulate, autonomous.

She recalled fondly how she and mum had bonded as grandmothers when Ian and I brought our daughters home from hospital.

“Do you remember when we first met in that small 4th floor flat, Betty? We were so excited to go to see the triplets and they were so beautiful. And hasn’t it been a joy to be their grandparents. They’ve grown into such special and adventurous young women. Then, when Milo arrived, we started from the beginning again.”

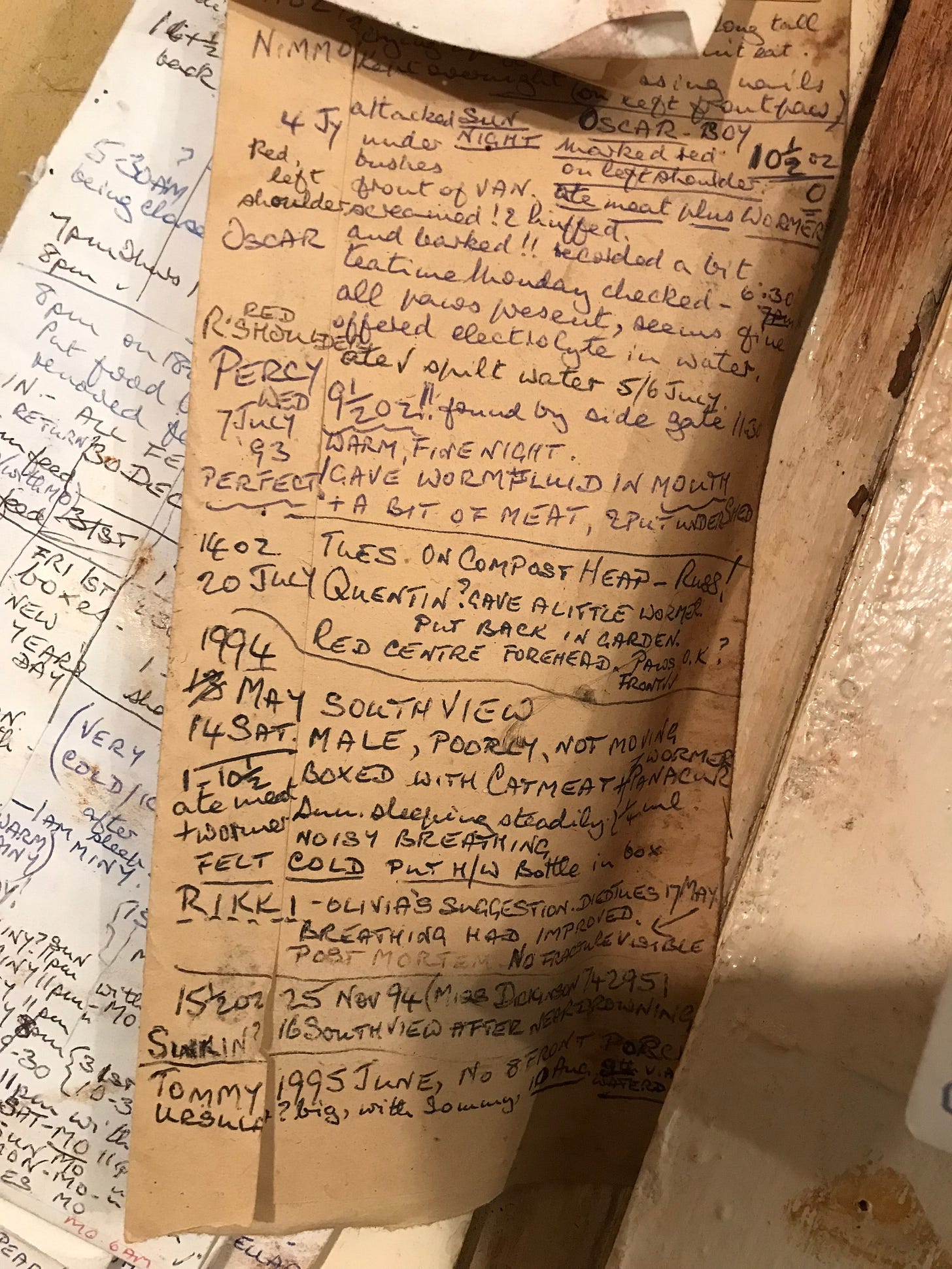

Here’s a short piece of writing by my mum that I found when I was clearing hers and dad’s house after they died:

By Betty Varley, September 1987

It sometimes seems that a tide of living is turning, ebbing before our eyes; as now, when tiny creatures which I have been privileged to care for, depart suddenly, leaving me grieving.

Strange, but perhaps swept out on that same tide, the departure of a dear friend fills me with sadness and wondering.

This has happened before: the sudden call of eternity to animal and human alike, at the same moment; it seems that the swelling of my heart has overflowed and weighed down the heart of my friend, who sank beneath its load.

Our need for others, for mutual support and encouragement, is underlying all life. It is as if we are all one, like a great land mass, which after many years sinks a little, so that the sea covers parts, leaving a multitude of little islands, each with the same soil, the same flowers, the same trees.

Those lovely people who enrich life with their warmth and generosity of spirit, who create wonderful music or beautiful things, are the treasures of Creation. Their influence for good spreads from island to island, bringing soft rains and sunshine, so that others too begin to bear fruit that is good, without trace of bitterness.

When we hold loved ones in our thoughts, wishing – and praying – for their happy success in life, it is as if power is transmitted to them, helping and strengthening for good. Sometimes I have been keenly aware of someone’s prayer lifting me when my own strength has failed.

It captures her world view: philosophical, spiritual, creative, and ultimately optimistic about humanity.

Missing my mum’s and dad’s voices prompted me to start writing this newsletter back in June. It struck me that it’s important to tell our stories while we can.

I’ve also learned that you shouldn’t wait for someone’s funeral to write a eulogy. Tell them what you treasure about them now.

© Wendy Varley 2024

How do you record your family’s stories or voices so that they’re saved for future generations? In the digital age, is it easier or harder to keep meaningful records over time? Please do comment below if you’re able.

I shared some of my dad’s childhood stories about growing up in 1930s Yorkshire here.

Thanks to everyone who read, liked, shared and/or commented on my piece about learning the facts of life last week. Wow, wasn’t it hit and miss, what we were taught or not taught?! Your comments mentioned baffling priests, scathing nuns, clueless teachers, and parents who put Claire Rayner’s The Body Book in the Christmas stocking, or left an informative magazine article out, and hoped for the best.

Some comments made me chuckle.

wrote:“This is great Wendy. Such a minefield. I recently strayed into what probably should have been parental territory with my granddaughter over a contemporary book about puberty called What’s Happening to Me? We got to the page about how making a baby actually happens. Very good – straightforward and clear. Saying it exactly how it is. Her response was ‘So you did this thing with grandpa twice?’”

Clicking the heart and/or sharing this piece will help other people find my writing.

Thanks for reading.

If you’ve read this far and haven’t already subscribed, I do hope you will!

Or, if you wish, there is a Wendy’s World tip jar:

Until next time!

"We called mum The InterBet, because of the speed with which she could disseminate family, local, or world news sitting by her landline phone." This made me laugh so much, it could have been a perfect description of my mum. What a lovely piece, it's made me think about how often I am annoyed with my mum but also how much I will miss being annoyed by her when the day comes. Better cherish her now.

Lovely piece. Stories are the generational connective tissue.