How were you taught the facts of life?

My mum had a stash of information on the topic, though I didn’t find it until 2022 when I was clearing the house after she and dad died. (At the same time as I found my nana’s contraceptive quinine pessaries, with their opaque instructions.)

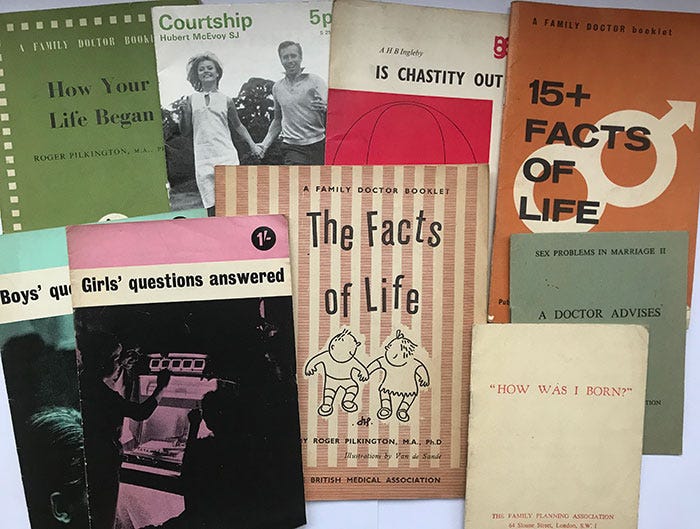

I’m guessing from the 1950s graphics that the pamphlet in the middle of the photo above is among the oldest.

The Facts of Life by Roger Pilkington, MA, PhD, published by the British Medical Association, starts out promisingly: “There is always an egg.” But then there are pages and pages about banana flies and wallabies:

“Probably you have seen a wallaby at the zoo, and if you are lucky you may have seen a mother hopping around with a baby poking its head out of the bag too.”

Chapter 3, The Meaning of Mating, starts with chickens, moves on to fish and frogs, ducks, newts, sheep, penguins, sandpipers and even bower birds:

“These preparations are called ‘courtship’ and perhaps the strangest and loveliest kind is found among the various bower birds.”

OK, David Attenborough, but what about humans?

Nope. The chapter ends, cryptically, with mention of dogs sniffing each other as they pass on the pavement, then concludes,

“Altogether the whole business of mating is very ingenious and carefully planned. And if this were not the case, then animals of every kind might never be able to raise their young creatures.”

He goes on to describe boys and girls, using sexist stereotypes:

“If you’re a girl, I hope you’ll be beautiful, because a beautiful girl can make somebody very happy.”

He’s talking inside and out: a pretty face is a bonus, but essentially, be kind, ladies. And “If you’re a boy, I hope you’ll be strong and courageous.”

Nowhere in the booklet titled The Facts of Life does Roger Pilkington describe how humans mate. The message is: you don’t need to know. Come back when you’re older.

His other booklet in the pile, How Your Life Began, is more scientific and picks up the story as sperm swims to ovum, but neatly skips the bit about how it got there.

By contrast, the tiny pamphlet, How Was I Born?, published by the Family Planning Association in 1955, wraps the whole thing up in a paragraph:

“Many mothers find it more difficult to explain the father’s part but when these questions come up they will have to be answered. The child can be told that all new creatures have to have a mother and a father and that the father has seeds called sperms which he places in the mother. These come throught the penis, which he puts into the vagina, this passage which they have already been told about. There the sperms swim up and join the mother’s egg in the womb and there the baby begins to grow. After some months the baby is big enough to be born.”

I think this is probably how my mum explained it to me when I was little.

When I was about six years old, my friend’s mum invited me to watch (with my own mum’s permission) a TV programme showing how a baby is born. It was matter-of-fact about depicting childbirth. I found it fascinating.

A couple of years later, our neighbour, Trisha, gave birth to her baby at home. My mum burnt the placenta for her in our fireplace, but first showed it to me and my sister, so we could see what had connected mother and baby during the pregnancy. I was struck by how spongy and meaty the placenta was, and how blue and rope-like the umbilical cord.

When I was nine, I was round at another friend’s house. She was far more worldly-wise than I was and told me that, for sex to happen, the woman has to “open her legs”. Now this was new information. I hadn’t thought much about the logistics.

Biology lessons at my secondary school in the 1970s covered the science in a very rudimentary way, but there was no sex education as such. And yes (surprise!), there were teen pregnancies. I remember one girl in my class was “up the duff” by her parents’ lodger at 14 and had to leave school.

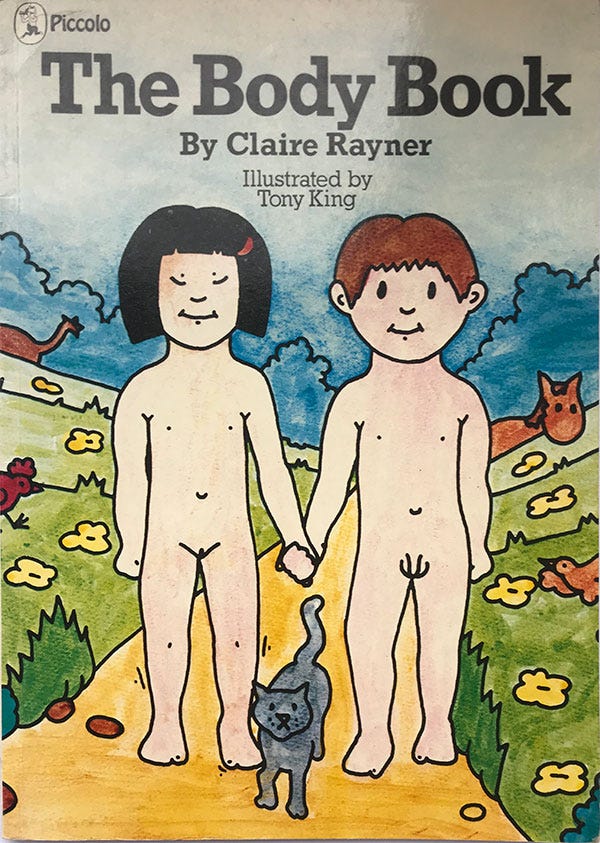

Sorting out bookshelves the other day, I came across two books that I used to explain the facts of life to my own children: The Body Book by Claire Rayner1, illustrated by Tony King (Piccolo, 1978); and Being Born by Sheila Kitzinger2, photography by Lennart Nilsson (Dorling Kindersley, 1986).

Being Born shows in photographs how the baby develops in the womb.

“It is not the story of what happens when a baby brother or sister is born,” explain Kitzinger and Nilsson in their introduction, “but about what a child could see, hear, feel and do deep inside the mother’s body, and about the baby’s experience of birth.”

The “narration” is second-person:

“Once you were in a small, dark place inside of your mother’s body, floating in a balloon of warm water.”

It’s a helpful book during pregnancy, too, far more useful for understanding what’s happening week-to-week than being told, “Your baby is now the size of a grapefruit.”

The Body Book covers everything from respiration, to digestion, through to growing old and dying.

Its chapter on ‘Growing and Changing and Making new people’ is admirably concise and accessible.

If I include the illustrations from that chapter, I might get reported for showing an erect – albeit cartoon – penis. Suffice to say, it gives an accurate description of the sex act, then Rayner adds:

“This is a special grown-up way of loving someone very much. It is the most loving sort of cuddle there is for grown-ups.”

My triplet daughters took in all this information.

Diary excerpt, 23 October 1992

The girls [aged five] watched the film Koyaanisqatsi with me last weekend. I told them that I first saw it with Ian before they were born; before I even knew I was going to have a baby.

“Well, had you and daddy done that special cuddle?” Alex asked. (A Claire Rayner useful term for sex.)

“Yes, but if a man and lady like each other, they often do that special cuddle just because it's fun; it doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll have a baby,” I said.

“Does it depend on whether they’ve got their trousers on?” said Alex, and then burst into laughter.

Sex Education at their primary school wasn’t covered until they were in Year 6, aged 11. Parents were invited to view the film, ahead of it being shown to the children.

Diary excerpt, 5 March 1998

The Sex Ed video was quite explicit and a bit of a laugh. Miss A said we were the noisiest group who had ever watched it (and there were only four of us: three mums, plus a grandma).

There was an actual baby being born, a very gory birth with a bloody great enormous baby emerging after a lot of effort.

“Blimey, it’s huge, it looks like an 11-pounder!” I said.

“This could put some of them off for life,” Caroline said. “It’s bringing it all back to me! Thank God it’s over.”

“In my case it was, ‘Just two more to go, Miss Varley!’” I laughed.

Then there was the sequence about sexual intercourse. The inevitable lumpy-faced, rosy cheeked, boggle-eyed cartoon characters suddenly appeared – so ugly they couldn’t be like anyone’s parents.

These pug faces get close and it’s explained that love-making usually begins with kissing, and then, within the context of a very loving relationship, they proceed to “stroke each other all over, because it feels good”.

“In your dreams,” interjected Caroline, and we fell about laughing.

Oh, and then the woman has an orgasm… every time, apparently.

The film footage was all spiky, short-haired women in dungarees flopping open their maternity bras (even when the baby’s nowhere in sight).

It was okay, but rather 1980s and dated (because the film was from the 1980s).

It was far more explicit than I’d anticipated. The girls are quite excited now, because I’ve made it clear that it shows real people (most of the time) and you do get to see a naked man and a naked woman (very self-consciously getting out of bed, so you can see the difference between a boy’s and man’s body and a girl’s and woman’s body). The guy has quite a big todger, actually, which appears to shrink when they suddenly turn him back into a cartoon in order to show what’s going on inside his and his partner’s bodies.

I’d better get a new hand-mirror, because we’re all supposed to be cool about looking at our own genitals.

When Miss A told us we were a noisy group, I said, “Well, we’ve got a lot of memories to share!”

By the time my son was at school in the noughts and 2010s, the Sex Ed materials had been updated somewhat.

Diary excerpt from mid-2014

M [aged 12] came home from school complaining that “The sandwiches ran out at lunchtime.”

“What did you have, then?”

“A cake and a drink. But it didn't matter. I didn't feel like eating much after the assembly we’d had.”

“Was it the ‘relationships’ assembly?” I asked, having been forewarned by letter that this year’s round of sex and relationships education was looming.

“Yes. It was gross.”

“How?”

“They showed us pictures of what you can catch from having unprotected sex.”

“Ah.”

“There was ONE funny bit where they said you mustn’t worry about a condom being too tight. You can blow it up to twice as big as your head and it won’t burst.”

“Handy to know.”

“Yup.”

“Have they at any time during Sex Education mentioned that sex is (or ought to be) enjoyable?” I asked.

“No, never. Though it’s pretty obvious from TV programmes that it’s meant to be enjoyable. I think at school they emphasise the disgusting stuff to put people off.”

He tells me now that the best Sex Ed class was when he was 14 or 15 and his Science teacher started by asking everyone to call out all the words they knew to do with sex and bodies and he’d write them on the board. Nothing was off limits.

“It got all the silliness out of the way at the start, so he could get on with the lesson.”

When I worked at Just Seventeen magazine in the mid-1980s, we gave away a free booklet called Just Ask3, and also published The Just Seventeen Advice Book4, expanding on the ever-popular Advice columns.

Re-reading them, they gave really informative, sensible and accurate guidance, which any teen now would benefit from.

By the 1990s, reproductive technology meant that “Where did I come from?” did not have just one answer.

I was curious to know how parents who had babies by IVF, donor insemination or surrogacy answered the question and wrote about it for the Independent newspaper in 19945.

Julie, who had her daughter by IVF said,

“I think what she understands herself is that she’s special, that it took a long time for mummy and daddy to get her …

“The other day she overheard me talking and said, ‘What’s an egg collection?’ It only needed the briefest explanation. I said, ‘That’s when the eggs inside a woman’s tummy can’t meet the sperm and they have to take the eggs out to meet the sperm.’”

Maybe that sounds just as feasible to a young child as being the result of mum and dad having a “special cuddle”, because, let’s face it, none of us want to think too hard about that!

© Wendy Varley 2024

Over to you: Were you taught the facts of life – or did you have to rely on the school of life? I’m aware it could be a sensitive topic, so only share what you’re comfortable with.

Please do comment below if you’re able.

Thanks to everyone who liked, shared and or/commented on last week’s piece, Hey Google: Cats. It was wonderful to read your views on children and technology. I was delighted to hear that I am now six degrees of separation from Kenny Loggins, after

commented that her mum used to teach his daughter violin!Clicking the heart and/or sharing this piece will help other people find my writing.

Welcome to those of you who’ve newly subscribed and if you’ve read this far and haven’t already subscribed, I do hope you will!

Contributions to my tip jar are also welcome!

Until next time!

Claire Rayner (1931–2010) was a British nurse turned advice columnist, TV presenter and novelist. Mum of journalist and food writer, Jay Rayner.

Sheila Kitzinger (1929–2015) was a British author of books on childbirth and parenting and a natural childbirth activist.

Just Ask, edited by Louise Chunn, came free with an issue of Just Seventeen in 1985.

The Just Seventeen Advice Book, edited by Jenny Tucker, published by Virgin in 1987.

“Where did I really come from, Mummy?” by Wendy Varley, The Independent, 26 September 1994, p18.

This is great Wendy. Such a minefield. I recently strayed into what probably should have been parental territory with my granddaughter over a contemporary book about puberty called What’s Happening to Me? We got to the page about how making a baby actually happens. Very good - straightforward and clear. Saying it exactly how it is. Her response was “So you did this thing with grandpa twice?”

I remember finding out a book about human reproduction at home when I was not a child but not yet a teenager. It had drawings and one of them showed a man and a woman with the man inside the woman. When I saw that and realised what was happening I thought, "Whaaaaat? It goes inside???" For some reason I thought human reproduction happened a bit like polinisation and that it was enough to touch the surface 😂