I was astonished to recently come across this 10-minute Arts Council film from 1971 about sculptor Rolanda Polonsky, a diagnosed schizophrenic who produced profound art about religion and the feminine experience during her 35-year stay at Netherne Hospital in Surrey.

I met her when, after my A-levels in 1979, I left my home in South Yorkshire to volunteer for nine months at Netherne, helping out with activities for the long-stay psychiatric patients.

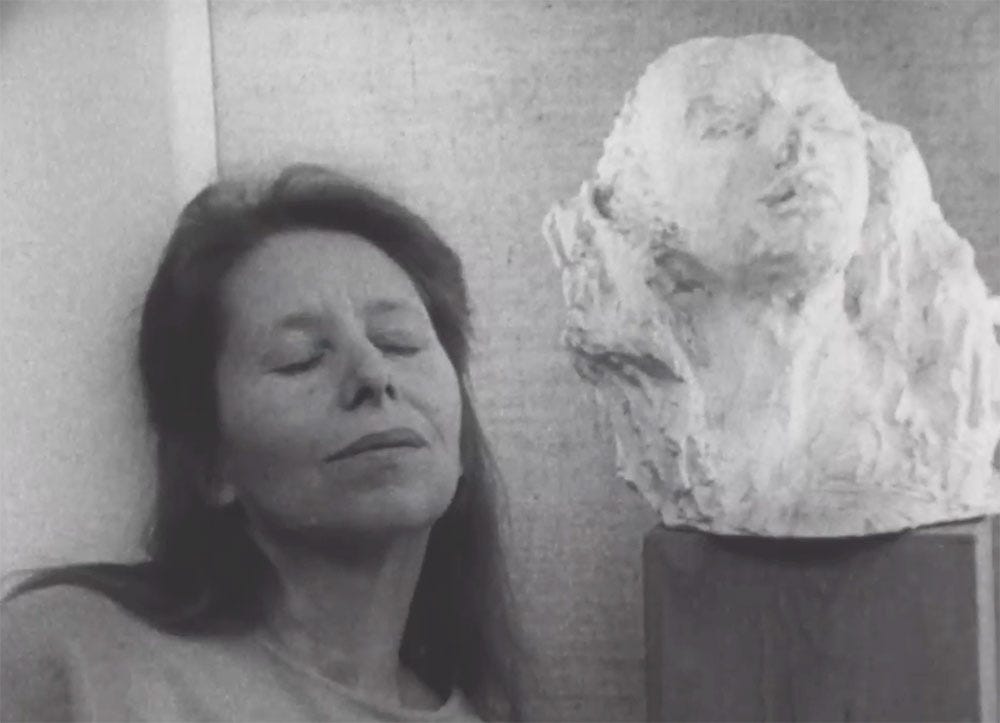

The resident who most fascinated me was Rolanda, rumoured to be an exiled Russian princess (or descended from one). She was elegant, soft-spoken, clearly well-educated, and an extremely talented sculptor – as you can see from the film.

She and another patient/artist, Martin Birch1, would hold court for some of us Community Service Volunteers (CSVs) in the summer house in the vast hospital grounds, offering us tea in filthy cups. Their friendship seemed entirely platonic and intellectual, borne of a shared a love of culture. Classical music wafted from a radio, and they each talked about the world in their own way. Both were diagnosed schizophrenic, and I struggled to follow the thread of their conversations, but it seemed to come from a place of wisdom.

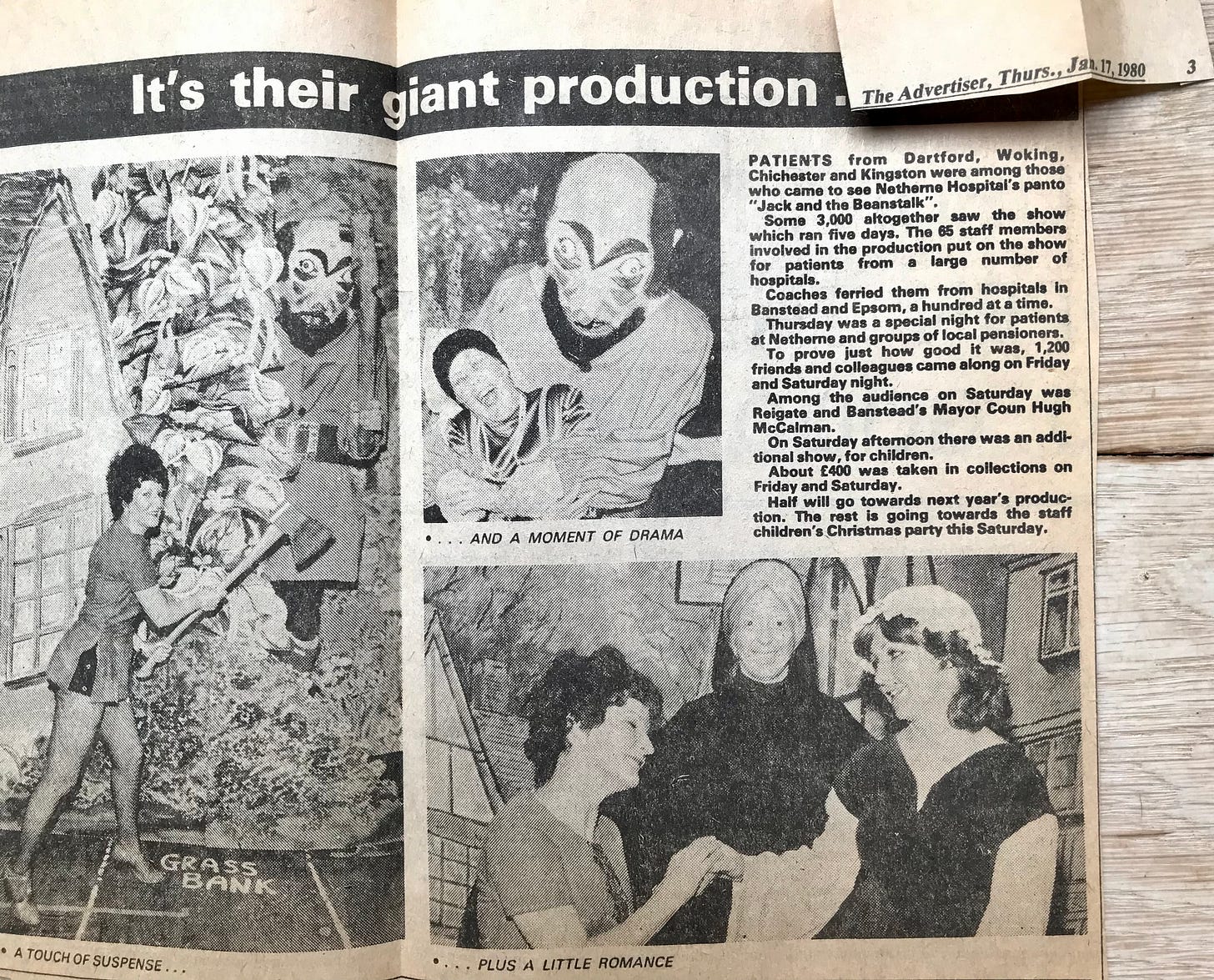

Martin wore a brown suit, was balding with straggly brown hair, glasses, and a cigarette permanently in his mouth, his teeth and fingers stained yellow with nicotine. He could be cantankerous and was sometimes banned from the art therapy studio for being disruptive. Rolanda, by contrast, was utterly serene. I don’t recall either of them attending the bingo nights or Come Dancing evenings we volunteers helped organise, or showing up to watch the annual Netherne panto*. I got the feeling they thought that was a bit beneath them!

I often wondered about Rolanda afterwards. Why had she come to be at Netherne and stayed there for so long? (She’d been there for more than 30 years by 1979.) Was she actually ill, or just institutionalised? And what became of her? I knew the hospital had eventually closed in 1994 and become part of a new housing development, Netherne-on-the-Hill.

Finding my teenage diary with mentions of Rolanda and Martin prompted me to do some digging. I found a Netherne Hospital history group on Facebook, which led me to the film about Rolanda, made eight years before I arrived there.

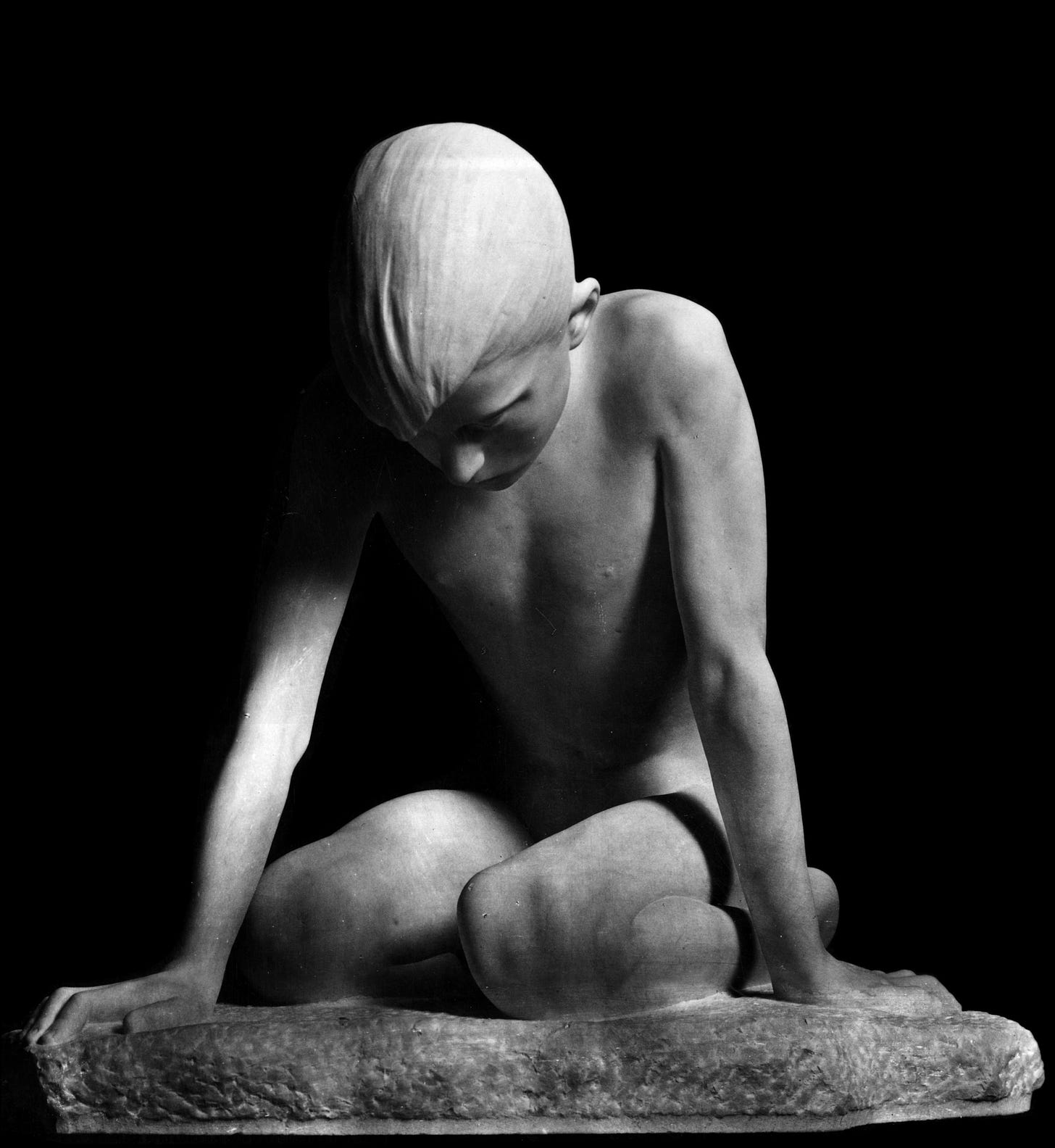

It’s extraordinary to see her, exactly as I remember her, presenting some of the art that she’d produced while in the hospital: a drawing of the Last Supper, with the body on the cross depicted as a woman, because “in my humble opinion, the woman has more crosses in the world than the man”. A sculpture of the face of “a girl who has just lost her virginity. She’s so surprised by the sensual act of man, that she doesn’t know what to think or what to do. She’s hell and heaven in this moment, thinking back of her whole life of the first years, when you don’t know and you are an innocent. And suddenly she’s grown up, and that is this portrait, of this moment.”

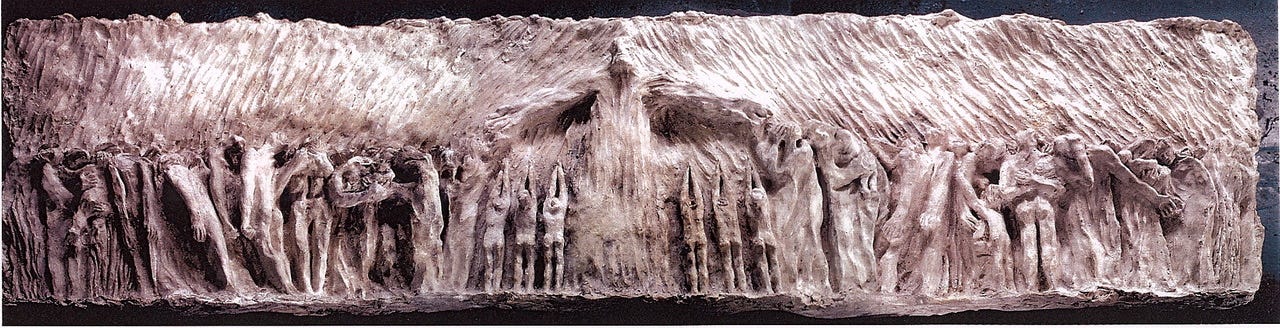

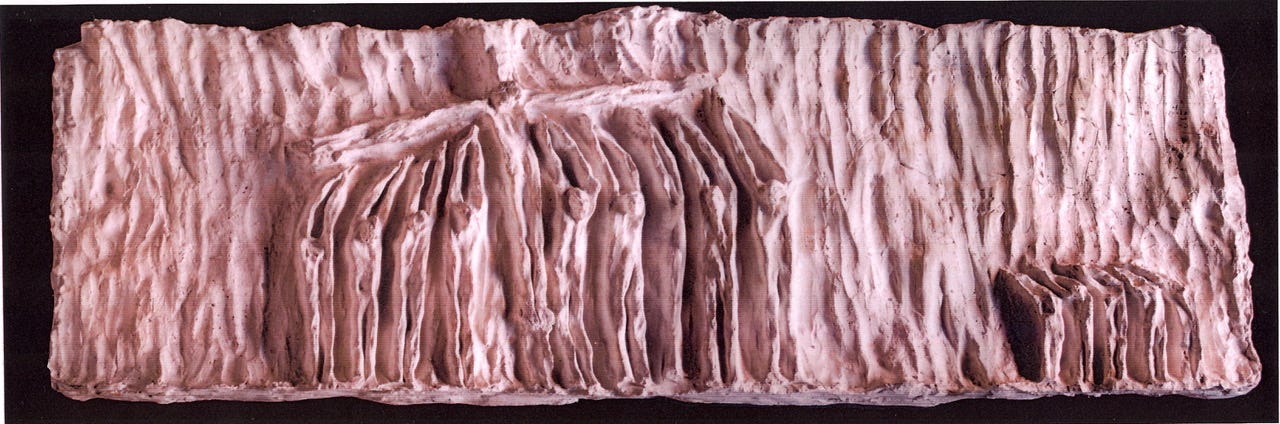

Her extraordinary series of large-scale religious sculptures for the hospital chapel titled Stations of the Cross, include the one at the top of the article, and this:

The film led me to academic Clair Wills’ 18th November 2021 essay in the London Review of Books about Netherne Hospital, titled Life Pushed Aside. Wills’s own mother and grandparents had worked there and, as a child, she had freely roamed the corridors and grounds during school holidays. She delves into Netherne’s history, the impression it made on her as a child, her fear of “opening the wrong door”. She describes the daily experience of psychiatric patients, including treatments we would now consider barbaric, such as lobotomy, induced insulin comas and electro-convulsive therapy (ECT). She also covers the more progressive move towards art therapy, which was pioneered at Netherne by Edward Adamson from 1947.

Clair Wills had seen the 1971 film about Polonsky and had traced her story, as far as she could.

Rolanda was born in Rovereto, northern Italy, in 1923 into an upper-middle-class family full of musicians, singers and philosophers. Her degree was in political science, but as a young woman she was already an accomplished sculptor. Following a breakdown during her twenties, she was admitted to Netherne Hospital where she stayed for 35 years until her sister eventually rescued her, “in effect, shamed by a doctor who asked her: ‘Why do you leave your sister in this place?’”

In 1982 or ’83, Rolanda left Netherne and moved to be with her sister in Paris. Several years later, she returned home to Rovereto to live in a convent, cared for by family. She died there in December 1996.

In her essay, Clair Wills had presumed Rolanda to be a lonely figure while at Netherne. “I am haunted by the figure of Rolanda Polonsky, walking through those hospital corridors,” she wrote. “What is it that she wants me to see that I do not want to see? What is it that she wants me to know?” She speculates that what Rolanda says in the film when describing her art perhaps relates to personal trauma.

I messaged Clair Wills to thank her for her article, which joined so many dots for me, and share my own memory of Rolanda and Martin in the summer house. She was heartened to hear that Rolanda did not spend all her days in hospital as a hermit.

She put me in touch with the Chair of the Adamson Collection, psychiatrist David O’Flynn. He has spent the past 13 years being custodian of, and finding a permanent home for, what remains of the vast collection of art that was created by patients at Netherne between 1947 and 1981, when Adamson retired. Much of it is now held by the Wellcome Collection in London.

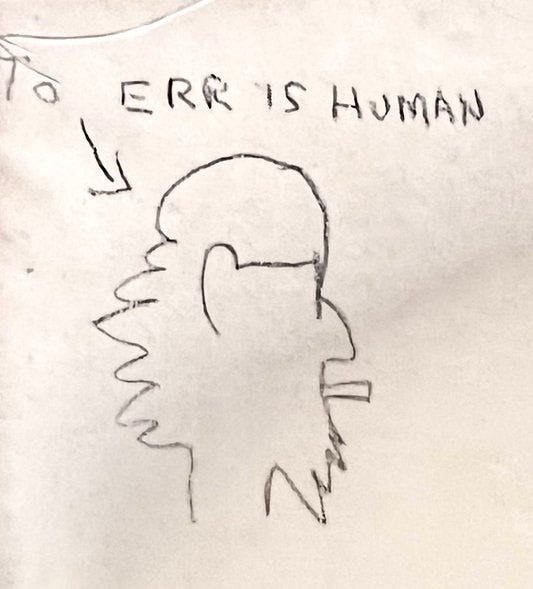

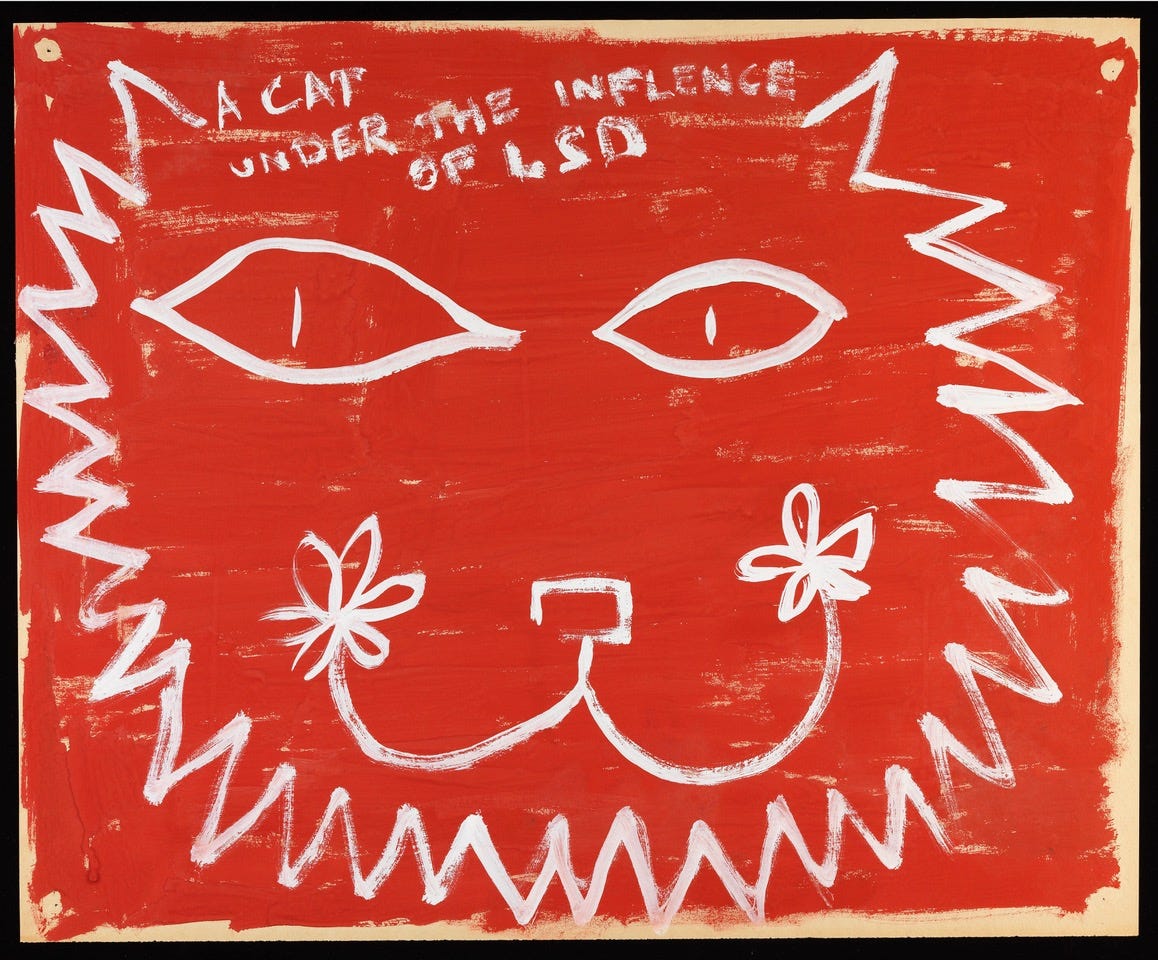

O’Flynn, too, was thrilled to hear my memories of Rolanda, and to hear about her friendship with Martin Birch. Birch’s work – cleverly cartoonish – is also part of the Adamson Collection, but O’Flynn had previously known nothing of his life.

David O’Flynn told me that there was a retrospective exhibition of Rolanda's work at the Civic Museum Rovereto in Italy just last month (May 2024), where some of her later drawings appeared alongside neoclassical sculptures she produced as a young woman, which are astonishingly accomplished.

Also – more serendipity! – he was about to meet Rolanda’s nieces, who are helping to piece together her history. Hearing from me that she was not a totally lonely figure while at Netherne has been a real comfort to them. They are amused by the “Russian princess” rumour. Apparently, that was very in character.

Rolanda’s story is still unfolding, and the Adamson Collection is discussing how to conserve for the long term her Stations of the Cross sculptures, which she produced while at Netherne. She had hoped to cast them in bronze, but they remain in the original hand-worked clay.

It’s tremendously gratifying that my dive into the history of Netherne and digging through my memories has had such deep meaning for other people: a reminder that it is often the right decision to hang on to your teenage diaries!

© Wendy Varley 2024

Postscript: After first sharing this Substack post, the Adamson Collection did further research into Martin Birch: Born 1935 – Died 1982.

My mum was a trainee nurse at Netherne in 79/80! She still has a diary from that time too, full of poems she wrote about working there.

This is a great piece Wendy. I’m so pleased that Rolanda has been recognised in some capacity and of all those serendipitous connections.

I feel I need to go and spend some time at the Wellcome Collection too. They hold so many stories.

One of my first jobs as a teenager was as a cleaner at the local Psychiatric hospital. A huge Victorian building plagued by rumours of barbaric treatment and hauntings. It’s also now flats.

I imagine it was a strange experience to volunteer there, but the world was ver different then?