When I walk into my home office, I pass the sailmaker’s stool that belonged to my great-grandfather1, and sometimes imagine him sitting there. I have no photograph of him, but considering how dinky the stool is, I guess he was a small man.

He was a merchant seaman and sailed on the Thermopylae, sister ship to the famous tea clipper The Cutty Sark. Colour-blindness meant he remained a sailmaker rather than becoming a sea captain. You can see the two grooves either end of the stool worn by rope. In my desk drawer I keep his sailmaker’s palm, with its inbuilt thimble.

He was a drinker, and my grandfather’s response was to be a teetotal Methodist. After serving in the army in WW1 grandad became an office clerk. His vice was smoking a pipe (though of course there was no awareness of smoking’s link with cancer in those days).

After my maternal grandparents died in the 1970s, my mother kept everything of theirs that she could cram into her campervan to bring home. Her parents had hung on to some of their late parents’ belongings and so I have inherited ephemera dating back to my great-grandparents.

In Japan, ancestors are worshipped and are thought to hang around as spirit protectors. I’m not sure how I’d feel about mine tuning in to current events. What would you reckon if yours were watching?! Would it be a comforting idea, or just plain spooky?

My grandfather’s tobacco tin is on my desk. Ogden’s St Bruno Flake. I remember it stationed alongside his rocking chair at his and Nana’s council house in Rockferry, next to a tin of delicious penny toffees.

The tobacco tin contains some stamps he’d saved inside an ancient Milky Way wrapper which, now I unfold it, is more fascinating than the stamps: “Read this – it’s about FREE PRIZES!” It came with collectors’ cards. Collect all fifty and you could send off for a “magnificent clasp knife”, a doll in costume, a tuck box, or an enlarged photograph of your favourite film star!

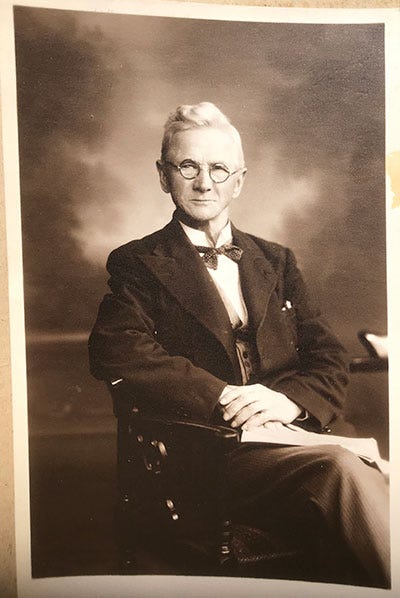

I have the diary of mum’s mum’s dad, dating from 1905. (Edwin Thompson Allen, 1866-1951.) He emigrated to Brazil and back as a young child:

“As a child of six years, I remember my mother (in a foreign country, having left all friends, and being without that fellowship that she had been used to in England, being surrounded by those who knew not God;) trying to lead her family in the right way, by having the Bible read on Sundays.”

Brazil was not the land of plenty his parents had been promised and they stayed only a few years.

I have a photo of his father, Charles Allen, washing mussels at Moreton Shore on Merseyside, some time after their return. Of his mother, Catherine (née Naylor), I know that: “She was a brick. Ooh, she went through some suffering.” That was the verdict of my Great Aunt Florrie (the oldest of Edwin’s daughters), who I spoke to in 1993 when she was 102, recording our conversation on videotape. Recounting what she had been told about the family’s emigration to Brazil, she said:

“Well, they had nothing to eat. One baby died and my father said my grandma had to go up into the mountain at night and dig a hole and bury little Tommy.

“They had chickens later on and they found they were going and so they took watch and there were monkeys! A whole row of monkeys. One would snatch the chicken, but it wouldn’t run off with it like you’d think. They would pass it on to the next monkey, and from there on to the next monkey. It was quicker than running off with it. Cunning!”

Back in Birkenhead, Edwin trained to become a watchmaker, got married and had four daughters. He became a fervent born-again Christian who harangued his children and grandchildren about heaven and hell.

I transcribed some of his diary in 2015 and shared extracts with my family. I was surprised to find he had a sense of humour. My aunt – remembering him drilling her on the bible when she was a child – was not amused and replied by email:

“When I saw his name and photograph I felt quite sick in the pit of my stomach. It brought back such awful memories. Father wouldn't have him in the house.

“Today I decided to be brave and open the enclosure. Reading of his antics didn't endear him to me, I'm afraid, just reinforced the feeling.”

I’m sure I’ll return to Edwin some time because his diary is fascinating, once you get beyond the religious ranting, which is hard to decipher. He has had an inter-generational impact, and not just on my branch of the family. I know, because I’ve exchanged notes with my second cousins. We connected because of our interest in family history and all roads lead back to this fire and brimstone great-grandfather we all share.

In 1946, looking back on his long life, he writes that his encroaching blindness ruined his watchmaking business, leaving him in debt:

“I lost all business, and she died, hopeless [his wife Ellen died in the early 1930s]. She told me, it was when she found I was going blind: no hope.

“Don’t think me wise. I have done the most stupid things at times. A friend said, ‘You have never been paid enough money for the work you have done, or you would not be in debt at all.’ Very comforting.”

Thanks to my mother saving everything, I discovered that my Nana Ada (Edwin’s second-oldest daughter) worked at Port Sunlight soap factory and played football for their women’s team while the men were away during WW1. And I know what she used as contraception.

I have few details about my Varley forebears, who were a much tidier bunch. They include a Sheffield tram conductress, milkman and clogmakers (the “clogs” actually being miners’ workboots).

All my ancestors were such “doers”. I suspect if they are looking on protectively, they’d be baffled by the sedentary nature of modern life and would be chivvying me to take a screen break.

Have you inherited anything odd from past generations? Is there someone notorious in your family’s past? Please do comment below if you are able. I love to hear what you think.

The wisdom of age…

My son (23) was talking to Ian and me about how differently he looks back on his adolescence now he’s a teacher. “My students are so sure they are right! And I was just like them! Gah!”

Ian half-remembered a quote, which I’ve realised is Mark Twain’s:

“When I was a boy of 14, my father was so ignorant I could hardly stand to have the old man around. But when I got to be 21, I was astonished at how much the old man had learned in seven years.”

Wise words.

Thank you…

(and possibly a tissue warning)

… to everyone who read my piece The Vigil last week, and particularly to those who shared their own reminiscences of vigils, or of not being at a loved one’s bedside when they died and the sense of regret that can go with that. It’s a privilege to read personal reflections on such an intimate topic. There’s no doubt that sharing memories of grief helps with processing it.

I published it on Tuesday evening rather than my regular Wednesday, as I felt it couldn’t wait. While I was writing and nursing a grotty cold, Ian was keeping vigil at his mother’s bedside, which was what sparked my reminiscence about my dad’s death.

Hours after I published it, Ian’s mum, J, died peacefully in the hospital’s palliative care ward, following a long illness.

I’ve mentioned J a couple of times, most recently in my new year piece. I’d visited her in the nursing home and found her smiling, watching The Sound of Music on TV. She disagreed with my opinion that the jilted baroness deserved some sympathy. She was Team Maria all the way.

My November 27 piece, The InterBet, was mainly about my own late mother, Betty, but it’s also about J, who has been such a rock in my life, since I met her in 1986. Simply the best, most supportive matriarch.

Ian and other members of our family were with her when she died, singing show tunes (songs from The Boyfriend) at the moment J chose to depart. She was always into musicals and am-dram, so it was very “her”.

It was not the only vigil going on in our wider family. We were all hoping for the full recovery of baby T (my first great-nephew), knowing from the outset that he was poorly and had a tough road ahead. Sadly, he died on Monday aged just seven days. It feels wrong not to mention, as he and his parents are so much on our minds, and even the briefest lives should be remembered.

I appreciated on Substack this week Margaret Bennett’s tribute to her late sister, Carrie.

Thank you for reading. Clicking the heart, sharing and/or commenting below all helps other people find my work.

If you’re enjoying my writing, please do subscribe, if you haven’t already. At the moment, nothing on Wendy’s World is behind a paywall. I really appreciate some of you taking out a paid subscription to support my writing, or popping something in the tip jar. Free or paid, though, I’m delighted to be sharing my writing with so many people!

Until next time!

© Wendy Varley 2025

Tom Brown (1858–1929, mum’s dad’s dad)

I love this homage Wendy to the ephemera of stuff that stays when people die. It's good to think of these small things living on in your house.

And I love hearing about the lives of working people who have gone before, stories that would otherwise be lost. You tell your family's stories with such love and courtesy.

Loved all of this Wendy and so sorry for your losses. That's a lot.