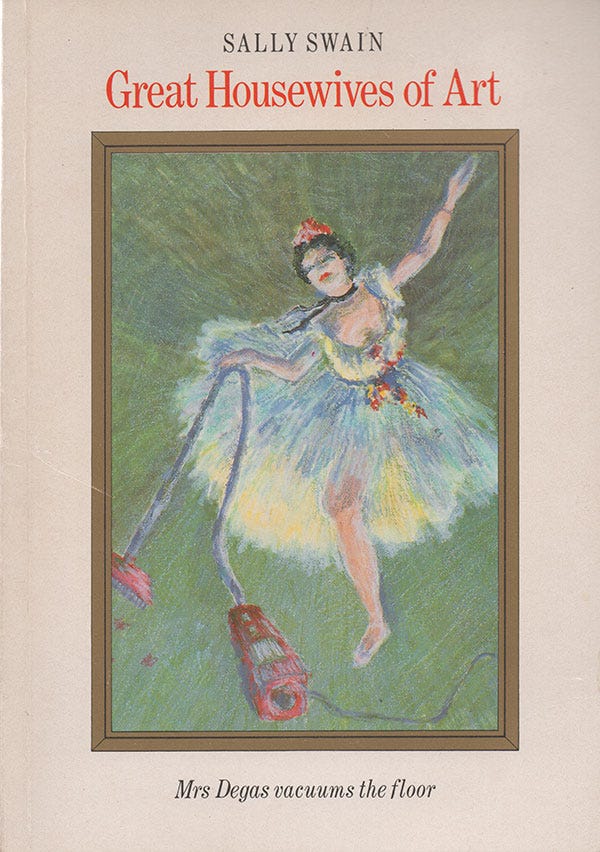

My friend Elaine gave me Sally Swain’s genius little book, Great Housewives of Art (Grafton Books, 1988) at a time when I was knee deep in nappies, juggling triplet toddlers with being a freelance journalist.

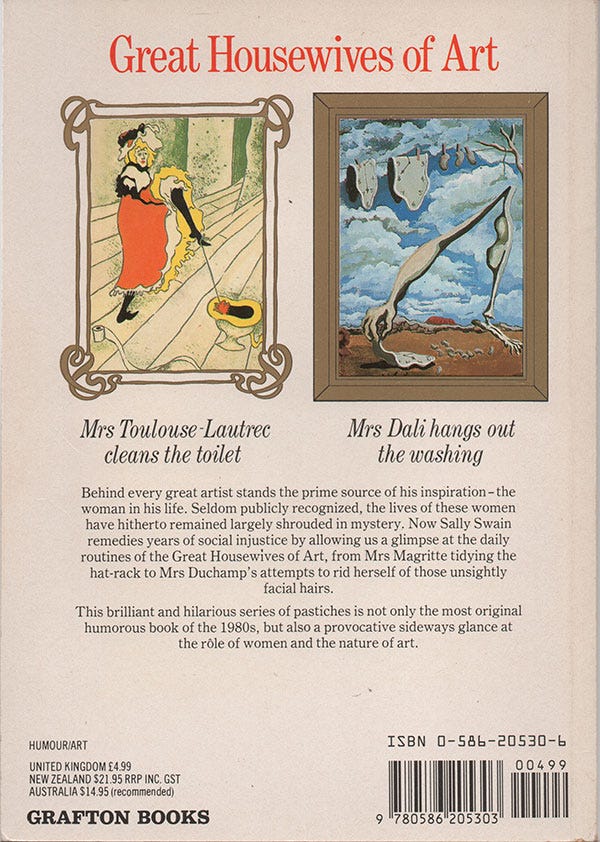

In clever pastiches of famous art classics, imagining what might have been going on behind the scenes, the cover shows Mrs Degas vacuuming the floor, while inside Mrs Chagall feeds the baby, floating over the highchair, spoonful of baby food in one hand, feather duster in the other; Mrs Monet cleans the pond; and Mrs Magritte tidies the hat rack.

“Why,” Swain asks in the introduction, “with so many female art students, do we still know of very few great women artists? And take the women behind the great male artists – what do we know of their lives?”

Art history is full of men. When I did A-Level Art in 1979 the only woman who cropped up in the art history module was 1960s op artist, Bridget Riley, with her dazzling monochrome spots and zig-zags.

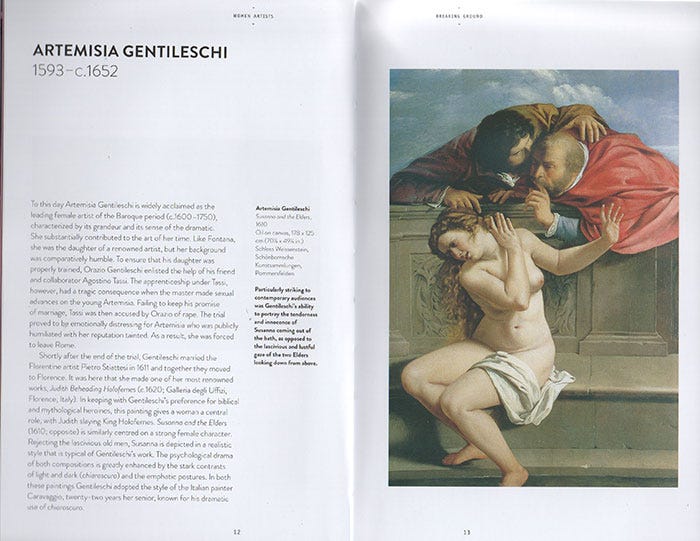

When I visited the Uffizi Gallery in Florence years ago, with its several hundred years-worth of classical Italian art, I played “spot the female artist”, and found precisely one: Artemisia Gentileschi’s gory depiction of Judith Beheading Holofernes.

There’s an entry on Gentileschi (1593–c1652) in Women Artists by Flavia Frigeri (Thames & Hudson, 2019) which my daughter Becky gave me for Mother’s Day. Artemisia did not have an easy life, being sexually assaulted by her art tutor and then finding that her reputation was sullied. I can see why she was drawn to paint Susanna and the Elders (below). In the bible story, Susanna confronts the Elders for spying on her and they threaten to blackmail her if she spurns their advances. She refuses them and ends up in court.

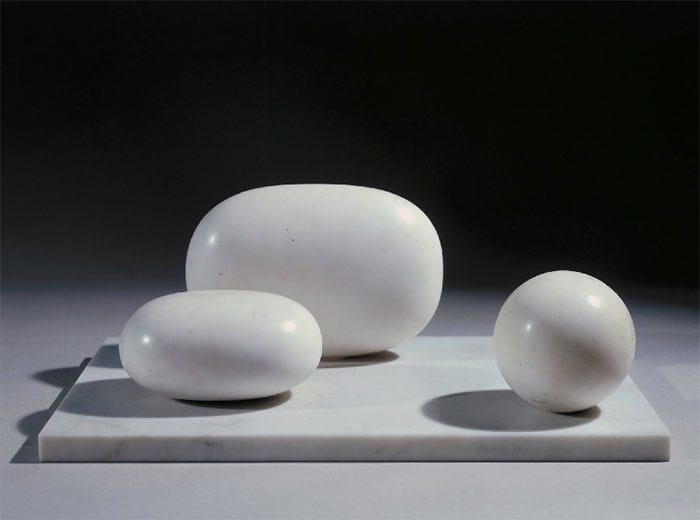

Barbara Hepworth (1903–1975)

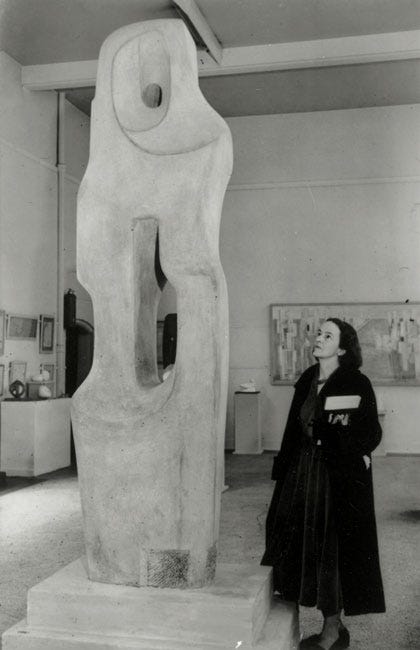

I was fascinated to learn when my daughters were little that the renowned modernist sculptor Barbara Hepworth had had triplets – two girls and a boy – in October 1934. (She already had a four-year old son.) She created the sculpture Three Forms (displayed in Tate Britain) soon after the birth of her triplets. She wrote:

“When I started carving again in November 1934, my work seemed to have changed direction, although the only fresh influences had been the arrival of the children.”

Woah, back at work within a month?! I know we’re meant to let the art speak for itself, but I wondered how she’d continued to create it. For a writer, the essentials are relatively simple: notebook + pen + time + inspiration (or deadline!). Theoretically, not too tricky to manage around an infant or three. For a painter, it gets messier. But a sculptor? You have to add in a whole host of extras: a studio, hunks of rock, chisels and hammers, and chips of sharp stone or wood flying. You have to dare to take up space.

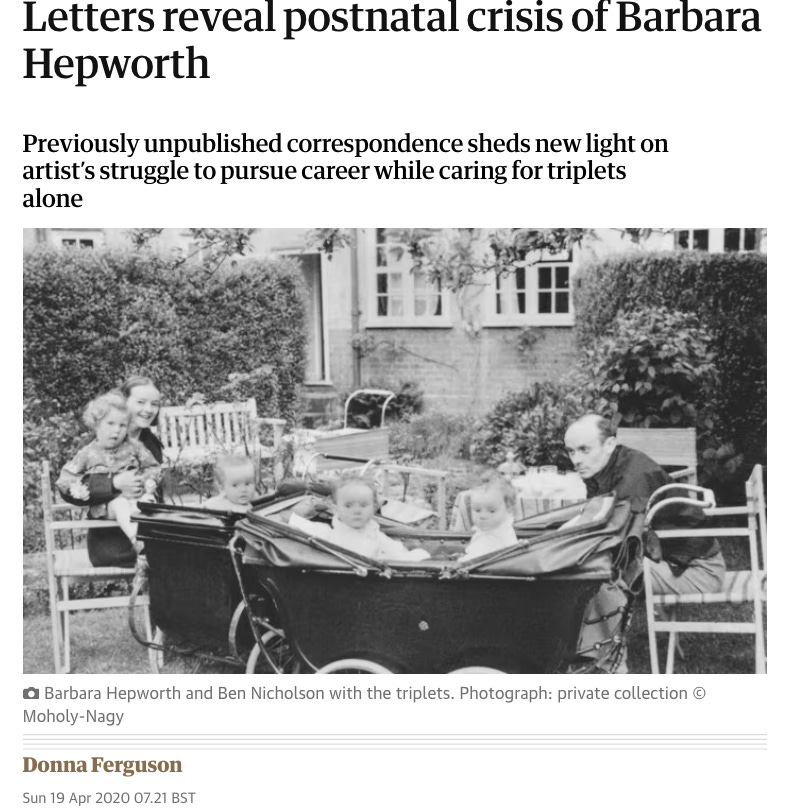

It wasn’t made any easier for Barbara when the triplets’ father, artist Ben Nicholson, left her caring for the babies in their cramped Hampstead flat while he returned to his first wife, another talented artist, Winifred Nicholson, in Paris, with whom he already had three children.1

Barbara solved the childcare dilemma by letting a nursery training college two miles away take care of the babies from the ages of four months until they were more than a year old, visiting them there, as this 2020 article by Donna Ferguson in The Observer describes.

‘She told a friend: “I’m not fit to live with unless I can do some work – even an hour a day keeps me civilised.”’

Later, she found ways to adapt her studio to the children’s needs, so she could combine her work with caring for them.

‘Often, Hepworth found integration between art and childcare. She excelled at schedule management and found she was able to “carry the creative mood” through “the chores & drudgery”. At other times, particularly as the Second World War compounded strains on the family, she expressed creative frustration: “If I didn’t have to cook, wash up, nurse children ad infinitum I should carve, carve & carve.”’2

She was prolific, making around 600 sculptures during her lifetime.

WWII left her despondent about machine-age warfare, and she was against nuclear weapons. Her art was her connection with life and landscape, her “consolidation of faith in living values”.

Her oldest son, Paul, died in an RAF plane crash over Thailand in 1953, aged 23. Her sculpture, Monolith, is a tribute to him and his navigator, who also died.

This BBC film made in 1961 shows Barbara Hepworth at work in St Ives, Cornwall, where she relocated in 1939.3 She died in an accidental studio fire in 1975, aged 72.

I’ve never heard her speak before and, though she grew up in Wakefield, Yorkshire, her accent is elocution-lesson Queen’s English. How I love her!

Over to you: Is there an artist whose life fascinates you, or has parallels with your own in some way? Do please comment if you can, I love to hear your thoughts.

A related article is about the time I met the sculptor Rolanda Polonsky when I briefly worked in a psychiatric hospital in 1979, when I was 18 and she had been a patient there for more than 30 years. Here’s the link, if you would like to read…

The mystery of Rolanda Polonsky

I was astonished to recently come across this 10-minute Arts Council film from 1971 about sculptor Rolanda Polonsky, a diagnosed schizophrenic who produced profound art about religion and the feminine experience during her 35-year stay at Netherne Hospital in Surrey.

Thanks for the appreciation for last week’s piece, Look up! Look Closer! Ironically, I spent the rest of the week in bed with flu, mostly asleep, so I’m in need of another dose of the great outdoors now I’m better.

Thank you for reading. Clicking the heart, sharing and/or commenting below all helps other people find my work.

If you’re enjoying my writing, please do subscribe, if you haven’t already.

I really appreciate some of you taking out a paid subscription to support my writing, or popping something in the tip jar. Free or paid, though, I’m delighted to be sharing my writing with so many people!

Until next time!

© Wendy Varley 2025

Hepworth married Ben Nicholson in 1938. They divorced in 1951.

Wonderful bit of art history. Of course I found a copy of that wives of the artists book in my mother’s loft in SoHo. My father told his second wife that if she wanted a baby that she should know he wasn’t getting up in the night or anything… (he was 60). My mother heard that story and laughed and laughed, “As if he’d ever have gotten up with you!” Love that you dug this up. Reminds me of the chutzpah of the artist Marcia Marcus who died last week. Here’s my related essay (shameless self promotion): https://twohouses.substack.com/p/art-and-the-families-228?r=nbjv0

You can bet when Cyril Connolly said “There is no more somber enemy of good art than the pram in the hall.”, he was only talking about the men.

I love both Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson’s work, but he did her wrong, and right royally so, didn’t he?

Great read, as ever, Wendy. Thanks!