The UK’s last coal-fired power station closed this week, ending 142 years of reliance on coal.

On the one hand: Hurrah! Britain is the first G7 nation and advanced economy to phase out coal. Renewables are taking up the slack.

On the other, I’m strangely wistful.

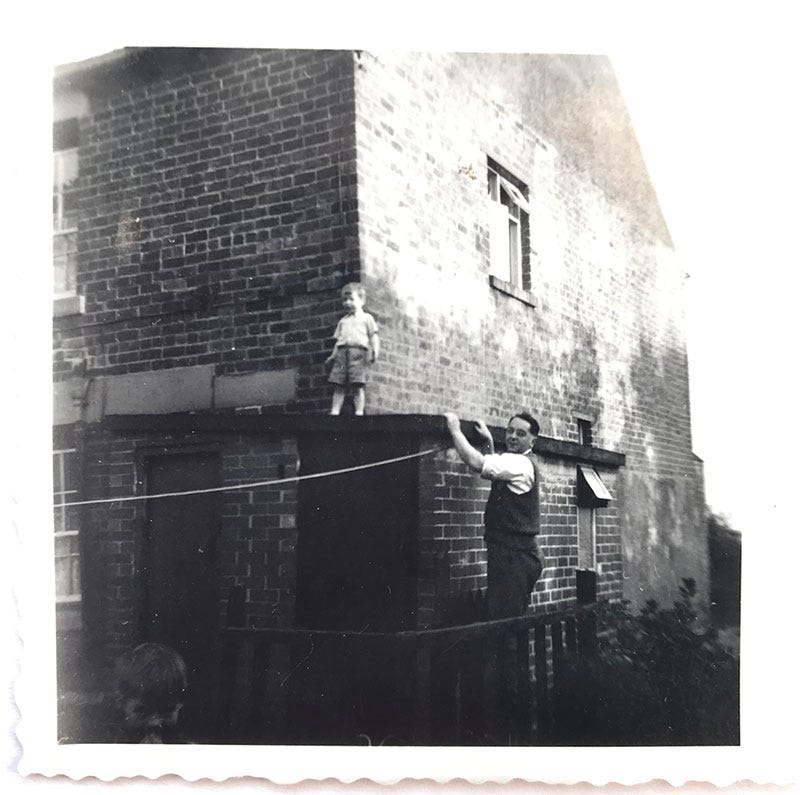

Coal was the landscape of my South Yorkshire youth. My Dad worked the lathe at the local colliery, maintaining the pit machinery. He’d rise before dawn each day and cycle to work, whatever the weather. (We didn’t own a car until 1971. You can read about our second-hand bubble car here.)

There was a coal fire in the living room, on which we’d toast bread in the evening, and an old-fashioned range in the kitchen.

We had a coal store at the side of the house, while my best friend, Vicki, at the top of the street, had a ghostly coal cellar, which we children would dare each other to venture into alone, in the dark.

At junior school, I learned how coal was formed from compressed fossilised plants. One day, we pretended to be Victorian children going down the mines1, the teacher covering a maze of desks with blackout curtains so that we could crawl underneath and witness the constriction.

Power cuts and miners’ strikes punctuated my youth. Our crooked house was built over a coal seam. Before it went to auction after my parents died, I had to obtain a mining report to show that its wonkiness was historic and not due to get any worse, all coal extraction in the area having long since ceased.

The pitheads and slag heaps have disappeared and the hills are green once more, interrupted now by industrial estates and distribution centres.

My diaries captured something of the mood of the times, as the nation grappled with reading by candlelight during 1970s power cuts and the UK coal industry entered its death throes in the 1980s.

Diary entry, Monday 28 February 1972 (aged 11)

On Saturday night, pop, the power went off! I went to bed early. I lit the little oil lamp in our bedroom. It gave a tiny light. The smell of paraffin filled the room. I am disappointed at having power cuts on Saturday night because I miss The Dick Emery Show.

I tried to read Gulliver’s Travels to Carol [my younger sister], but soon gave up. After a while we told stories to each other.

Yesterday we were on high risk, and we had another power cut, this time from 4–8pm. My friend Jackie was at our house. We played at ‘spooks’ in the front room. It’s exciting when we have power cuts.

The miners went on strike in January 1972 and that led to electricity shortages through the winter.

If you want to see how 1972 looked fashion-wise, here’s a pamphlet featuring the “Coal Queen of Britain” competition on its cover. The winner served as a brand ambassador for the coal industry.

The following year there was a global oil crisis, followed by more miners’ disputes.

In a bid to save electricity, Conservative prime minister Edward Heath introduced a three-day working week2 in January 1974 for non-essential services and businesses.

Excerpts from my diary, early January 1974 (aged 13)

I got up at 12 noon. Mum was asleep on the settee.

I did my dishes and when Dad came home from work at 3pm I did the ’tatoes and put the chops on while Carol did the sprouts and carrots.

After dinner, Carol and me made some paper flowers from Carol’s set. I watched Top of the Pops and It Ain’t Half Hot Mum then finished my poppy.

I did some loosening up ballet exercises then went into the front room to watch some of the talks about the miners’ overtime ban. A man from Dad’s pit was on, although I didn’t see him talking.

We kept laughing at the so-called big increases in wage that the government are offering in the stage three thing. In fact they aren’t taking into account in their figures that people are working one hour extra every night. All most people would get is £2.50 extra. So much for Mr Heath’s big increase.

Mum gave me a sleeping tablet so that I’ll be able to get to sleep tonight.

…

Mum brought Carol and me a cup of tea each to wake us up, however my sleeping tablet got the better of me and I went back to sleep.

Robin [my older brother] bought another David Bowie LP to add to his collection. Now he’s got Hunky Dory, Aladdin Sane and Pin-Ups.

I watched television: Kung Fu, Dad’s Army and the The Dimbleby Talk-In. David Dimbleby was talking to children about the state of the nation and even he thought the miners were already on strike.

Wednesday 16 January 1974

The Minister of Power says we have to save power by scrubbing our teeth in the dark which I think is daft.

The energy crisis led Ted Heath to call a snap general election in February of that year, which was won by Labour. The new Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, awarded mineworkers a 35% pay increase and the three-day week ended in March of 1974.

That was the year my parents installed a second-hand mint green Aga in the kitchen, fuelled by coke (smokeless fuel). My dad got a fuel allowance due to being a mineworker.

The Aga was much more than its ever-warm hob and ovens. It heated the hot water tank; it kept the kitchen toasty all year – more than was needed during the sizzling summer of 1976 – and it aired the washing on the pulley above. You’d sometimes have to duck under a bedsheet to check on the Yorkshire puddings. It became the heart of our home.

Fast forward ten years

Conservative PM Margaret Thatcher announced 20 pit closures in March 1984, which led to local strike action. Without a national ballot of members, different areas had different views: Nottinghamshire pits initially stayed open, while Yorkshire pits shut up shop.

Diary excerpt on the miner’s strike, 1984

I wrote this on a scrap of paper stuck into my diary, so I’m not sure of the exact date.

At an NUM meeting at Barrow Colliery, near Arthur Scargill’s headquarters in Barnsley, a pit engineer stands up and asks a question: “Why don’t we have a pit ballot on whether to stay out on strike or return to work?”

He knows that in Scargill-land it’s a dangerous question.

The engineer’s question causes uproar. He’s shouted down and told to get out. He stays, but things go dim after that. On relating the story to his family, he can’t remember how the meeting ended or how he got home.

The union only wants to hear from those who believe all pits – economical or not – should continue to be worked.

The miners who support the union and go on picket duty are paid from union funds. They picket seven days a week, even at pits where there’s been no Sunday working for years. But then, wouldn’t you, if you knew that this was your only source of income; the alternative being a few pounds of social security money?

Those who are against the strike stay at home, unpaid, and keep quiet, for the most part. It’s not very safe, in South Yorkshire, to do otherwise. They read the papers and they watch the news, where “the miners” are simply “the pickets”. But then, who’s to know anything about miners against the strikes, who are quite sensibly lying low.

Living in London, I’ve heard a lot of support for Arthur Scargill from the “democratic” left wing. I’ve been asked to support the miners by attending benefits and giving to collections. “Aren’t you gonna support your old man?” they ask.

I know that my Dad won’t get a penny, and all I can say is, “He wouldn’t thank me for it.” And I try to explain why.

Even in my own diary, I was distancing myself, not wanting to spell out that it was my dad asking for the pit ballot.

Dad was a pragmatist. He was a Labour voter and he supported workers’ unions. But he knew the coal was running out.

After he spoke up at that meeting, there were nuisance phone calls in the middle of the night. He or Mum would answer and no-one was there. It was scary.

The miners’ strike rumbled on for nearly a year, until March 1985, when it was finally called off by the union.

There have been some excellent documentaries3 shown this year in the UK, to mark the 40th anniversary of the strike, and it’s good to hear the different viewpoints.

Dad was made redundant following the end of the strike, aged 57.

He eventually had the Aga converted to run on oil.

Pretty much every trace of mining in the area has gone now4, except for The National Coal Mining Museum, near Wakefield. I visited it once with my Dad and my young son. The volunteers who issued us with torches and helmets and took us below ground were all ex-miners. They made fantastic guides.

It was truly claustrophobic exploring those tunnels where coal was extracted. My junior school classroom “warren” had been a poor substitute.

Later, we visited The Big Pit National Coal Museum in Wales, where we bought this miner carved from coal. Now I’ve rediscovered him, I’m going to put him on the mantelpiece above the log burner.

© Wendy Varley 2024

Thanks to everyone who read, liked, commented and/or shared my piece last week about my “hotel dogsbody” coming of age summer of 1980. The comments were fantastic, thank you. Readers shared brilliant memories about the tricky jobs they’ve had, including drilling holes in pepperpots; being a stand-in snake dancer (hope we get the full story on that,

!); and a nurse assisting a surgeon and almost losing her finger.The cordon bleu “posh nosh” hotel menu also sparked memories. Pretty sure I’ll be returning to the subject of food nostalgia at some point.

wrote, “That menu is the stuff of dreams. It’s basically the menu that appeared in every Jersey restaurant in the 80s and why the two of us [her and her husband] wander the world perpetually disappointed by restaurants everywhere.”Back to this week: have you been part of an industry, or grown up in a place that was connected to an industry, to the extent that it felt part of your life?

Clicking the heart, commenting and/or sharing this piece will help other people find my writing.

Thanks for reading. Till next time!

A law was passed in 1842 banning children under ten years of age from working underground.

More on the three day working week.

TV documentaries to mark the 40th anniversary of the miners’ strike include: Miners’ Strike, A Frontline Story, BBC, and Miners’ Strike 1984: The Battle for Britain, Channel 4.

The last deep coal mine in Britain, Kellingley, closed in December 2015.

A great post Wendy. I love your diary entries and feel I hear the younger you. I remember the power cuts and I think they went into the mid- late 70s too.

No family members in mining but it feels like the not so distant past but it’s so far removed from much of our industry now.

I remember for my art o level I painted a lot about the miners strike. I’d forgotten that.

Fascinating to read this. There’s no coal-mining history in my face that I know of, but my grandad worked on the railway and steam was still the thing when I was little. Coal was absolutely everywhere and part of the fabric of life. I remember the three day weeks and I remember the miners’ strike. Always thought that Thatcher vs Scargill was a contest of two almost equally unlikeable figures. He promised the mining communities that if they stayed strong they would win. They made horrendous sacrifices… and lost.