My “dogsbody” coming of age summer

Learning Northern hospitality working in a country hotel, 1980

I’ve known since 1980 I’m not cut out for the hospitality industry. I wasn’t exactly bad at it, I just knew once I’d tried it that I never wanted to do it again.

I took a job at a country hotel in North Yorkshire1 that summer because it offered board, lodging and a small wage for three months. I’d spent most of a gap year before university helping to run patient activities at a psychiatric hospital (a voluntary, live-in role). I was due to take up my university place in London that autumn. I did not want to go home in between. I was quite angsty enough, without having to skive off my parents and squeeze back into their cluttered house.

I spotted the ad for a “hotel dogsbody” in a magazine (that genuinely was the job description), wrote to the manager and got a letter back telling me I was hired and when to turn up. And that was that.

I arrived at the hotel in Grassington with zero experience of waitressing or hospitality and a smattering of inverse snobbery. I assumed all the guests had nice homes, plenty of money and that they had no idea how “real” people lived.

The hotel boss had a volcanic temper and reminded me of Basil Fawlty2.

Most of the other staff were locals and I noted my first impressions in my diary:

“Funny people here. Honest, blunt, basic. Overheard manure-mouth Sally* [16-year old waitress] saying today, ‘Ah, but if they’d really been at it for five hours, he’d have had to ’ve shot his load some time wun’t ’e? And if ’e’d shot his load, I can’t understand it if she i’n’t pregnant, ’cos they din’t use nowt.’”

A lanky, acne-ridden, 15-year old waiter called Mark asked me within hours of meeting me if I was a virgin. “I didn’t tell him. It would have been all round the hotel in five minutes if I had,” I wrote.

The hotel was in the heart of the Yorkshire Dales, popular with hikers, salesmen on the road and shooting parties. Shooting parties were the worst. Arrogant men, away from their wives, who thought comely young waitresses were fair game. They patted our bottoms, tried to coax us into meeting them one-to-one after dark, and filled up the kitchen with their pongy dead pheasants.

At first I was assigned to washing up, but as I was presentable and polite enough to deal with customers, after just a couple of days I was given a crash course in silver-service waitressing.

I had only ever seen this in films. Serving food from a large platter balanced on one arm, using only a fork and spoon in a pincer grip to dish up the food is very tricky.

Paired with “gobby Sally”, we were serving a table where two diners had ordered the fish (something large and flat, plaice, maybe). It had been filleted by the chef and neatly presented with the tail still attached, for us to divvy up.

Sally snatched it from the pass as she was the more experienced of the two of us, to demonstrate how it was done. She tilted the platter too much so that three quarters of the fish slid in a heap on the lady diner’s plate, with just the tail to offer her companion.

Sally clomped off to the kitchen in a rage (it was the era of vertiginous platform shoes) and we could hear her swearing from the dining room.

“It’s fine, it’s fine,” said the lady with most of the fish, when I offered to redistribute it, or return it to the kitchen to start over. Clearly, it was not fine.

The Menu

The menu was cordon bleu. What a revelation. I had never eaten “poncy French food” before. What the heck is Coquille St. Jacques au Gratin? I wondered. Then one day, there was a spare going at the end of the service. I was offered it and my mind was blown.

Ditto Fricassée of Sweetbreads. “It’s what? Offal?!” I poked at it suspiciously, then wolfed it down. It was gorgeous. As for the Tournedos du Chef, I had only once before eaten steak, treated by my aunt, and it was nothing like this melt-in-the-mouth morsel.

The first time a diner selected Cheese and Biscuits for dessert, I went to the larder to prep it and worriedly asked the chef, “Do you know some of these cheeses are mouldy?” I’d never seen blue cheese before.

The assistant manager gave us a lesson in portion control. When a diner requested “a little of everything” from the Hors d’oeuvres trolley, that could be a whole day’s calories right there. Boiled eggs smothered in mayonnaise, asparagus with hollandaise sauce, prawn cocktail, rollmop herring, vol-au-vents.

A “Selection of Sweets from the Trolley”, with its trifles and meringues and wobbly crème caramels, mille-feuilles and black forest gateau, meant “a little of everything” from there was asking for trouble.

Some of the waiting staff were mean with portions; some of us were at risk of sending diners straight to the cardiac unit. Hence, portion control lessons.

I learned to cut butter into cubes with a knife dipped in hot water. I’d prepare the curly toast for the breakfast baskets. It involved grilling white sandwich bread, cutting the crusts off, slicing the toast through the middle so it’s half-thickness, then toasting the white side so the now very thin toast curls up. You had to be careful not to let it catch fire.

The long shifts messed with my sleep patterns, so I felt either hyperactive or half-dead. A late waitressing shift could be followed by an early reception shift, with no time to decompress. Days off were spent walking the moors, channelling Cathy out of Wuthering Heights, or doing my laundry.

Here’s my diary entry from 14 July 1980:

Today is one of those where I want to run away and hide in a wardrobe and not be found. I feel tender.

Bought new blue jumpsuit in Skipton. At least had the confidence to try something fresh. But inside very raw. Sunshine, oh my God, sunshine in the sky and on the green ground and that makes me want to fly.

Sadly, back to the hotel. Guiltily nab meringue and cream from the kitchen. Go back for seconds and Mark nearly catches me. Feel like a startled rabbit and like a thief.

Have meringue in my hand and ironing to do over my other arm. Am suddenly so afraid of being seen.

Go into laundry room. But what if someone’s already inside and sees my meringue? Oh God, someone is inside, so I dump my ironing and run with meringue back to room and put it down. Then go back to do ironing.

It’s Billy who’s there. He looks cross with me. I cower.

“You didn’t tell me about that phone call for me, did you? Was it you who answered ’t’ phone?”

“Oh… Yes. Well, I knew you weren’t working, so I told him that and he said, OK.”

“Ay, but I were ’ere.”

“Oh… I’m sorry.”

He leaves me alone for a moment, but then comes back across.

“And if anybody phones again, you tell ’em, I’m porter, not washer-upper.”

“Pardon?”

“They were making fun at me ’cos you’d called me ‘Billy washer-upper’ on t’phone.”

“I didn’t know you had another title,” I said.

“Well, it’s not your fault, but I applied ’ere as porter an’ it sounds a lot better for a fella than ‘washer-upper’.”

“Oh, I’m sorry – it’s just that it seemed a sensible title to me.”

“Ay, well.”

Exit one very depressed Wendy. I was raw to start with and that cut in deep, mainly because so far Billy’s never said anything against me. [Billy had recently been in prison and no-one knew what for, so we were all a bit wary of him.]

Back in my room I scoffed down that meringue as if I were being watched by millions.

I gathered myself together and decided to go for a walk. Was out for an hour and a half. Lovely weather, sheep, cows, grass, scenery so beautiful and refreshing and here I am, feeling much better.

The front desk

By August I had been promoted to reception duties and bar work. I’d type up and run off the daily menus manually on the Gestetner3 machine.

A representative from Visa turned up to ask if we wanted a credit card machine and was promptly dismissed by the manager. He said that everyone paid cash or by cheque, thank you very much, and the hotel’s customers would never use such a device.

I learned how to work the hotel switchboard, all wires and sockets.

I told one guest as he came in for dinner that his wife had asked him to phone her urgently. He looked puzzled. After taking her call, he was in anguish.

“Is everything alright?” I asked.

“No… my dog’s been killed.”

“An accident?”

“Not really. I left it chained up this morning, thinking it would be alright. It strangled itself. The children found it. They were very attached to it. I don’t know what to do.”

“I’m so sorry.”

At that moment the restaurant manager turned up and asked “Would you like to go through to the dining room now, sir?”

Of course, he left dinner early.

“Would you tell the restaurant that I can’t face my meal?” he said.

Then he paced in and out of the hotel for a while.

I deducted the three-course dinner from his bill, without checking with my boss. It just seemed the right thing to do.

Making friends

The other staff initially viewed me with suspicion as I was From The South (of Yorkshire), but they gradually warmed to me. Jane was the only one with a car and would drive us to nearby towns on our nights off.

One evening, we drove to a town further away where we were going to a disco with her friends and would stay overnight. I wore my new jumpsuit and joined in with the seated rowing dance to Oops Upside Your Head by The Gap Band.

Chatting to two of Janet’s male friends it emerged that they were gay. One brought a girl along as he didn’t want to be queried about his sexuality.

It hadn’t occurred to Jane that her other friend, Mary (tall, fresh-faced, dressed in lumberjack shirt and jeans), was also gay. I shared the attic room with Mary that night and it was blindingly obvious that she was interested in me. I told her I had a boyfriend and she said she respected me too much to try anything physical. She hadn’t come out to her family or friends. We were up till 3am whispering and she told me how hard it was to be a lesbian in small-town North Yorkshire. Then her mum banged on the floor and told us to go to sleep.

I really did have a boyfriend. We’d hardly seen each other since sixth form, but technically we were still together, and I was trying to work out what to do about contraception for when we met up again. I’ve already mentioned this diary excerpt in my piece on the history of contraception, but I’ll repeat it here:

I rang up the family planning clinic from the phone booth in the residents’ lounge, to try to make an appointment.

Awful crackling line.

“What’s the nature of your enquiry?”

“I want to get an IUD fitted,” I whispered.

“I’m sorry, this is a very bad line. What did you say?”

“I want to get an IUD fitted,” I hissed.

“Sorry, I didn’t catch that.”

“I WANT TO GET AN IUD FITTED,” I bellowed.

When I emerged from the booth, a middle-aged couple had just taken their seats in the lounge to order a cream tea. They had heard every word.

Coming of age

I was in my room one night after a long shift, listening to XTC’s Making Plans For Nigel4 at top volume and singing along: “We’re only making plans for Nigel, We only want what’s best for him.” But I had to turn it off after the night porter banged on my door to complain that I was disturbing the guests. Here’s my diary entry:

12 August 1980

Music strums and drums and I am overwhelmed by its typicality of this age. I will think back on this music with nostalgia in years to come – it is music of the ’80s5.

I didn’t even realise I was in the ’70s growing up, and even less that the ’60s existed.

In a way, it’s a pity I didn’t get a good look at the ’60s from a more grown-up point of view. I think I’d have probably liked flower power and love and peace and all that.

And yet where did it go? Where does the spirit of the age go? The people are still here – people of the ’30s and ’40s and ’50s and ’60s and ’70s – but the spirit goes.

There was a feeling that summer of 1980 that I really was between the decades, and between the decades of my own life, my teens and my twenties. I was coming of age.

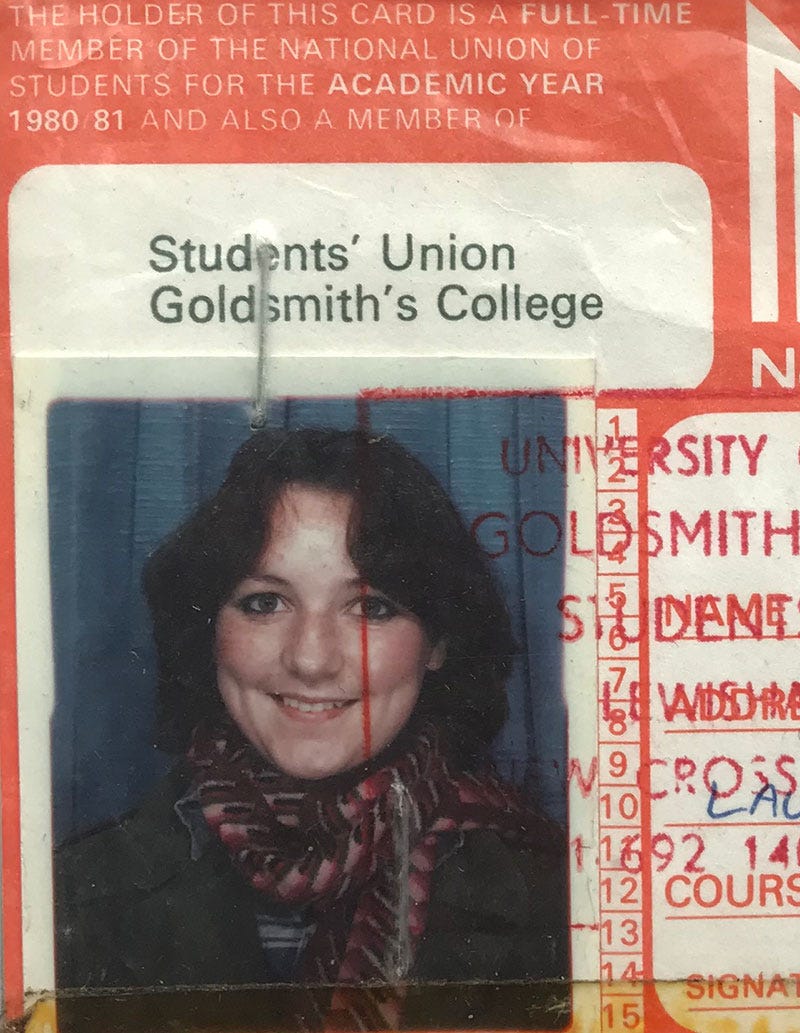

“I know I’m going to live magnificently,” I wrote in my diary, with echoes of what Mr Beeb says about Lucy Honeychurch in A Room With A View6. I hadn’t yet read EM Forster’s book. It came up on the English syllabus at Goldsmith’s later that year. But that’s another story.

*Some names have been changed.

© Wendy Varley 2024

Thanks to everyone who read, liked, commented and/or shared my piece last week about Waiting for Freddie Mercury. There were some wonderful comments.

I was inspired to write about my brief stint in hospitality after reading other Substackers’ entertaining pieces on the jobs they didn’t want. Two of the most recent were

(The Flagging Dad), on his worst job ever, doing telesales and (Ninki Substack) on all the menial and teaching jobs she’s had. Both recommended.What was your least favourite job? Let me know in the comments. And if you’ve written about it on Substack, or have read a memorable piece on the topic, please do feel free to share the link.

Thanks for reading. Till next time!

The hotel closed in 1988 and has since been converted into a care home.

Fawlty Towers was a 1970s TV comedy about a dysfunctional English hotel, starring John Cleese as proprietor Basil Fawlty.

A manual crank-handle roller printer. You could run off several copies at once.

While writing this, I wondered what happened to XTC singer/songwriter Andy Partridge. I found this fascinating Guardian article describing how he’s been affected by mental illness.

Making Plans for Nigel was released in August 1979, so pretty much on the cusp of the ’80s.

“If Miss Honeychurch ever takes to live as she plays, it will be very exciting both for us and for her,” is the quote from A Room With A View I’m thinking of.

I loved this read so much happening: the fish; the phone call; the dog; the request for IUD. Captivating story.

Funny, I’m working on one as well.

I’m not sure if I can post my least favorite job. I’ll just say briefly my two brothers came to live with me while I was in university and I need to make extra money so I could help them out while they were in recovery.

I took a job bartending.

I had no idea that there would be dancers or what kind of dancers would be the entertainment.

One night, a dancer didn’t show up, the one who danced with a snake.

I was asked to take her place.

That was my last night.

Most of the jobs I had I really enjoyed .

🌹

My first service-industry job was a lot more mass-market: a holiday-camp kitchen, where a typical service was for 500 or so guests often damp from the rain.

I was “on starters”, which meant our army-trained (and so incredibly organised) chef had laid out 500 silver bowls and I’d fill each with the regulation treat: up to 4 prawns, two leaves of lettuce, a sliced tomato and a spoon of Marie Rose sauce. Load about 20 onto a tray and one of the wait-staff (a couple of notches up the social status than me) would whisk it out to the salivating masses.

I can still picture the only guy who seemed to be lower-status: a giant washer-upper, elbow-deep in a greasy sink the size of a padding pool, obscured by the steam for hours at a time.