The original domestic goddess, Mrs Beeton

I imagined Mrs Beeton as a Victorian version of UK celebrity cook Mary Berry. I was wrong.

“I have always thought that there is no more fruitful source of family discontent than badly-cooked dinners and untidy ways,” wrote Mrs Beeton in the preface to her best-selling book, Mrs Beeton’s Household Management.

Badly-cooked dinners and untidy ways were a massive source of arguments in the home I grew up in. That’s why my mum so often consulted this 1680-page (plus adverts) tome, which lived in a corner of the kitchen cupboard throughout my childhood and was still there when I cleared my late parents’ house in 2022. It helped her navigate a domestic world in which she struggled.

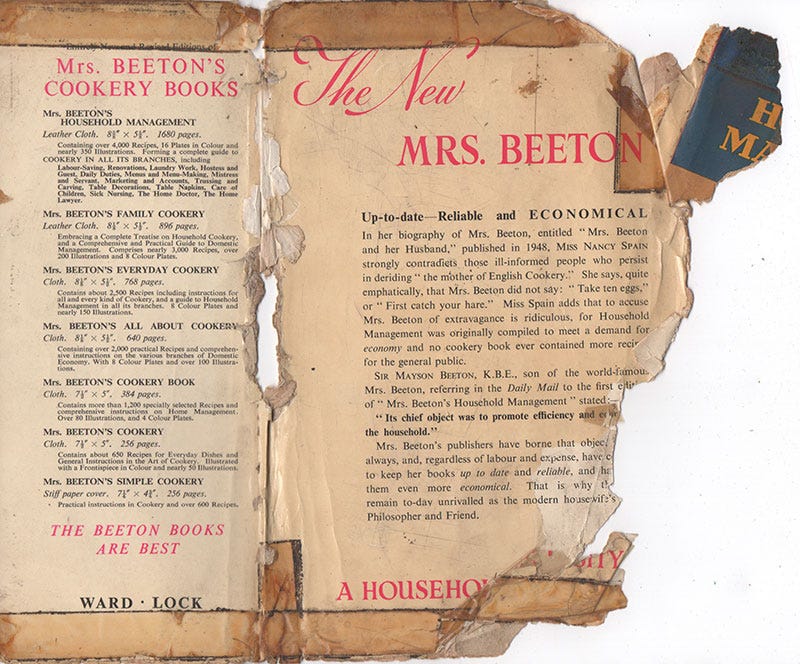

This battered half-a-dust-jacket of the “New” 1950 edition that Mum owned became a bookmark (waste not, want not). It marks a page of recipes for pheasant.1 I remember why it was there. Dad’s friend and colleague, Albert, from the colliery he worked at, was a poacher who eventually became a gamekeeper on the Fitzwilliam estate in Wentworth, Yorkshire. One day Albert strolled down our street swinging a brace of brightly coloured birds as a present for mum and dad. I’d never seen pheasants before, alive or dead.

Mum was flummoxed about what to do with the birds and turned to Mrs Beeton:

“Pluck and draw the bird, truss in the same way as a roast chicken, but leave the head on.” (Page 618)

I have no memory of us preparing or eating the pheasants, but I can’t imagine Mum would have let them go to waste.

I do remember the hare casserole. (Was the dead hare another gift from Albert? I’m not sure.) Mum was not at all squeamish. She had a scientific mind and decided to do a full anatomical dissection of the hare before cooking it. She gathered us children round to examine its organs and help remove the pelt, which we salted and pegged on an airing rack above the range to dry out. Its gamey smell eventually faded. The hare skin stayed there dangling next to drying socks for years. It was such a fixture, it stopped striking me as weird.

I didn’t enjoy the casserole.

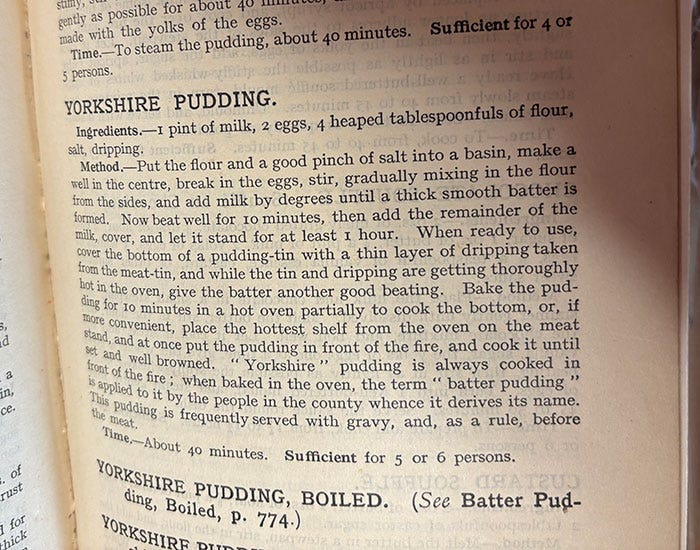

Other sections Mum marked with tissue paper were Beef, Pastry, Pickles, and Ice Cream. Beef caused a lot of rows, because Mum would forget it was in the oven and a good Sunday roast would be burnt. She was good at pastry and Yorkshire Pudding, though, and Mrs Beeton’s recipes are exactly the quantities and methods I remember her showing me.

Mrs Beeton advised on all sorts, not just cookery. She told you how to clean just about anything, from lizard skin, to piano keys, to pewter, to ostrich feathers. And there’s medical advice at the back, including on how to treat hysteria:

“The principal feature of the treatment consists in the separation of the patient from sympathetic friends and relatives; the confining of the patient to bed, not allowing her at first to read, write or even feed herself; and the daily use of massage. The diet for the first week or two consists almost entirely of milk, a teacupful being given every 2 hours. After a little while solid food is added to the dietary; a chop for example being given at noon, and toast and bread and butter with the milk.” (p1582)

The book acknowledges that men can suffer hysteria, too, and refers to wartime experiences as an example.

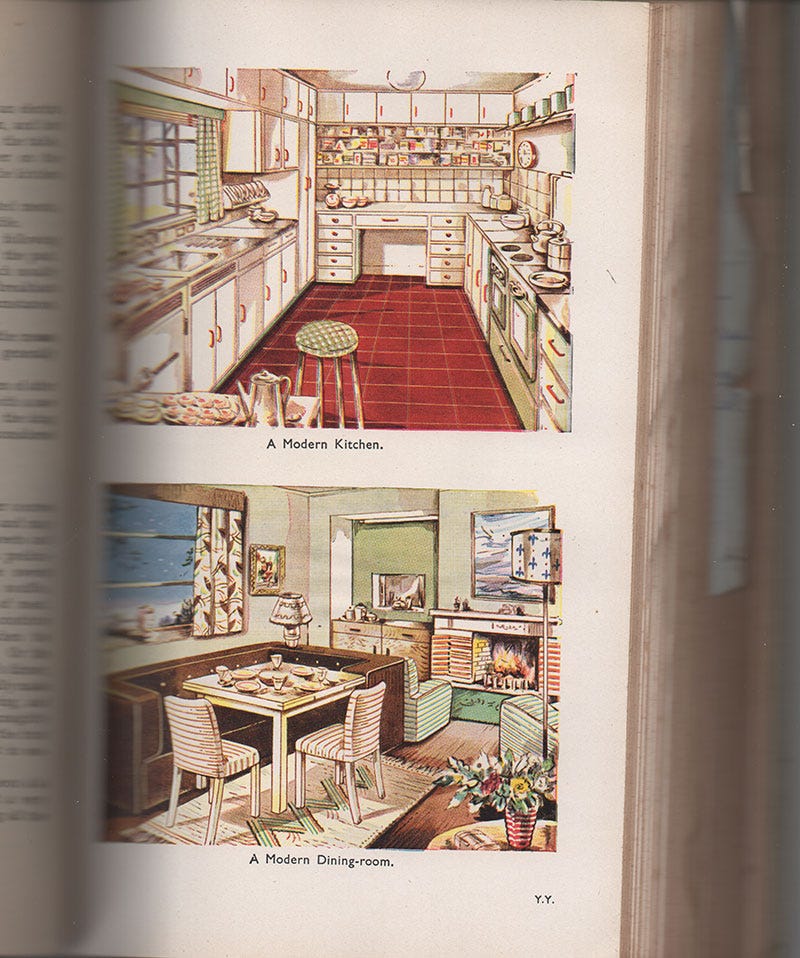

The original illustrations for Mrs Beeton were destroyed in a fire during WWII, so the 1950 edition was brought up-to-date, featuring zingy modern kitchens and dining rooms.

I imagined Mrs Beeton as a Victorian version of UK celebrity cook Mary Berry. (Mary just launched a new homeware brand to mark her 90th birthday.)

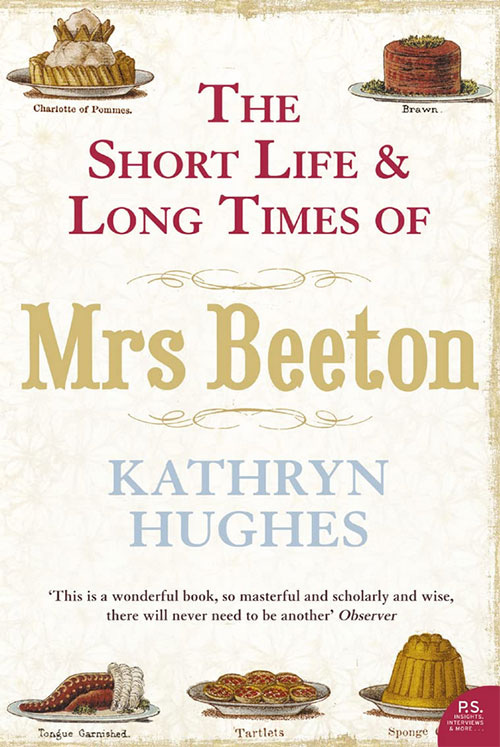

The reality, as I discovered when I read Kathryn Hughes’ excellent biography of her, The Short Life & Long Times of Mrs Beeton (2006, Harper Perennial), was very different.

Who was Mrs Beeton?

The eldest girl in a tribe of 21 children

Born Isabella Mary Mayson, 14 March 1836, Mrs Beeton was the eldest of the four children of linen merchant, Benjamin Mayson, and his wife, Elizabeth. Her father died when she was four and her mother then married a widower, Henry Dorling, who had four children of his own. Together, Elizabeth and Henry had a further 13 children, so Isabella was the oldest girl in a “tribe” of 21 and became her younger siblings’ unofficial nanny at an early age. Safe to say, she picked up a lot about household management.

Her stepfather was the clerk at Epsom racecourse in Surrey, granted a house in the grounds, and the racecourse grandstand became, on non-race days, the nursery space for the children.

Sent to Heidelberg in Germany for two years in her mid-teens as part of her education, Isabella learned French and German, became an accomplished pianist, and learned to make pastry, an interest she resumed when she returned to England.

Wife, mother, editress

Isabella married Samuel Beeton, publisher of The Englishwoman’s Domestic Magazine, in 1856, when she was 20 and he was 25.

She was soon contributing to the magazine, translating stories from French to English, and writing a cookery column, garnered from other cookery writers’ recipes. During the next couple of years, Isabella compiled what would become Mrs Beeton’s Household Management. It was initially published in 24 instalments, then as a single volume in 1861.

In addition to writing about food, Isabella became fashion editor of The Queen magazine, which Samuel launched in 1861. Its current incarnation is Harper’s Bazaar. She commuted into their London office and comes across in Hughes’ biography as meticulously organised and dedicated to her work.

She and Samuel had four children and, according to her biographer, she had a series of miscarriages between times. Their first son, born in 1857, died aged three months. Kathryn Hughes suggests that it’s possible Samuel had syphilis, which he’d picked up from a prostitute as a young man and unknowingly passed on to Isabella and she to the infant.

Their second son died aged three years. The third boy, Orchart, lived to old age and became a journalist. The fourth, Mayson, also lived to old age, but sadly, Mrs Beeton did not. She contracted puerperal fever (from infection introduced during the baby’s delivery) and died several days after his birth in 1865, aged just 28.

By then, the book was doing well, but Samuel was struggling financially and he sold the rights to Ward Lock & Tyler. From there, the Mrs Beeton juggernaut was unstoppable and it became an inconvenience to mention that Mrs Beeton herself was dead. The history of Isabella Beeton, the woman, was hidden behind the famous brand.

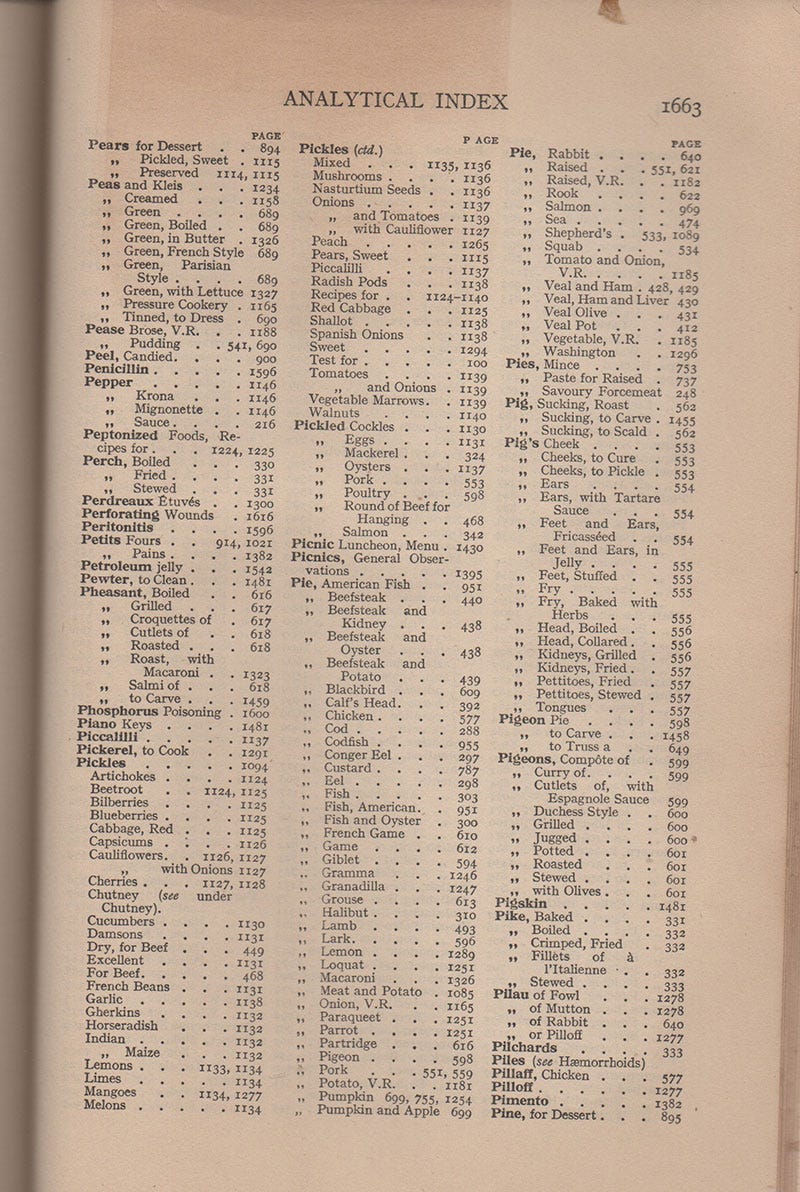

Her focus had been on producing a practical guide that helped women organise their households in an economical way, and that’s why it endured. This example from the index shows how comprehensive and nose-to-tail it was.

I don’t have the 1861 original to compare it to, but by the 1950 edition there are sections on vegetarian cookery and international cuisine. The dust jacket shows that there were seven other Mrs Beeton titles still in print at that time.

It’s Mother’s Day in the UK this weekend, and in my mum’s memory, I’m going to cook some Yorkshire Pudding, using Mrs Beeton’s foolproof recipe.

Over to you: Is there an essential “how to” book you can’t do without, or which featured large in your life as you were growing up? Please comment below if you can. I love to hear your thoughts.

Thanks to everyone who responded to my piece last week, The Dive: my Pacific panic. and for sharing your own comments about gung-ho moments that did not go to plan.

Clicking the heart, commenting and/or sharing this piece will help other people find my writing.

Thanks for reading, and if you haven’t already subscribed, I do hope you will!

Or, if you wish to make a one-off contribution, there is a Wendy’s World tip jar:

Until next time!

© Wendy Varley 2025

I always thought Mrs Beeton was like a Fanny Craddock type from circa WWII - thank you for such a thorough education!

My mum's culinary tome was The Good Housekeeping cookery book from, I'd guess, the early 70s. I always enjoyed cooking as a kid and I was a slavish devotee to that book for a couple of years. I don't really do cookbooks as an adult, but I've got a couple that I refuse to throw out. When I get a bigger kitchen they're getting their own easy access shelf.

What an interesting piece, Wendy! And the pheasant!!! Not hard to imagine that it's a nod from Mrs Beeton herself!